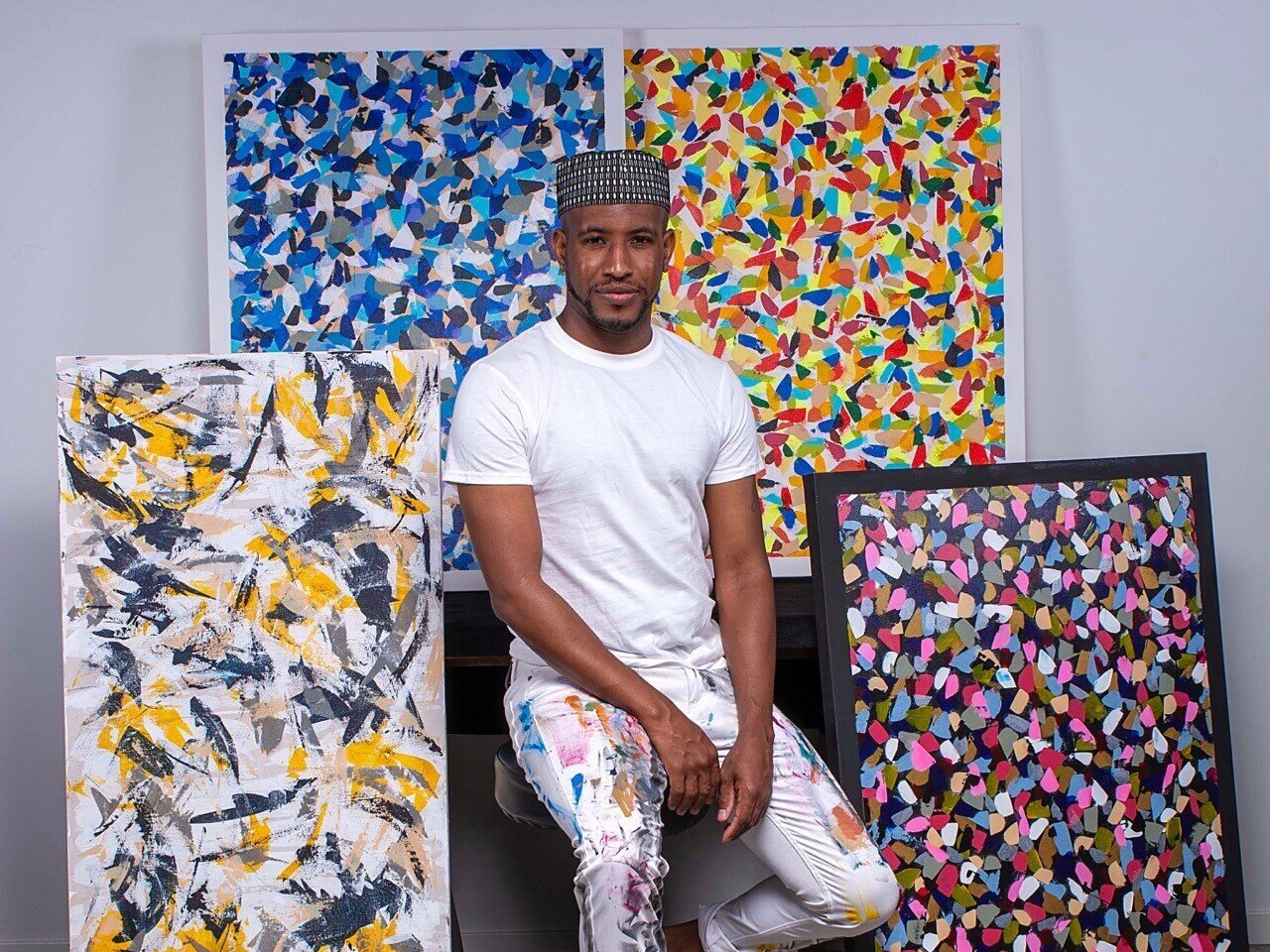

Abstract Artist Emmy Marshall Is The Epitome of Gay ‘Black Boy Joy’

Every time abstract artist Emmy Marshall, 36, sells a new painting he places a red sticker on the back of his bedroom door. So far this year, there are 52 stickers and counting. It’s one way the Atlanta native and openly gay artist visually celebrates his success, which doesn’t appear to be slowing down anytime soon.

“This train is moving,” says Marshall during his interview with The Reckoning.

“I don't know how these things are happening, but people find me and they put my name in hats and in rooms and conversations and people are reaching out,” he says.

Besides producing quality work, one theory the self-taught artist has for his recent success is his ability as an abstract artist to tap into the imaginations of art consumers.

“With principles of design, you're creating a piece of artwork and it's open to interpretation,” says Marshall. “I may have a meaning for what this means, but whoever purchases the art or is looking at it may see something totally different. And that is why it is really cool for me because you get to tap into other people's imagination,” he says.

With successful art shows, an abundance of commission requests, and an increasingly expanding social media following, Marshall’s career path and success seemed to come as a surprise to everyone but his sister Kenisha Daniel, who he says was an early supporter of his work. His mother, not so much.

“It wasn't until the work started really selling and being circulated around Atlanta that my sister saw and she was like, ‘Ma, he's selling a lot of stuff, he's doing well,” he recalls.

“My creativity has always been an outlet that I could run to when it came to that side of me. I never actually had any plans on coming out—only because you can’t see the light at the end of the tunnel. There’s just so many unknown factors.”

Marshall tells The Reckoning that this was a turning point for his mother who began to see his artistic talent as a gift worth pursuing.

"The fact that strangers are now buying my work. They don't know me, they're coming in because they see something that they think is beautiful. It is drawing them in from the streets,” he says. “My sister went back and told my mom and she was like, ‘oh, so this art thing is paying off now, huh?"

Marshall says he never let his mother’s initial lack of support deter him from pursuing his art nor did he take it personally.

“I always operate in optimism and anyone that knows me knows that's what I'm about. And I pour that into my work,” he says.

At that moment, a text comes through, causing Marshall to look at his phone. It’s from his mother. “Hi, son!” the text read. He smiles.

Choosing Freedom

It’s a small miracle that Marshall still finds a million and one reasons to smile given the contentious way in which he says he was “involuntarily” forced to come out as gay, and after two devastating losses in 2020. Through it all, he says art was his refuge.

“My creativity has always been an outlet that I could run to when it came to that side of me. I never actually had any plans on coming out—only because you can’t see the light at the end of the tunnel. There’s just so many unknown factors. I came out involuntarily,” he says.

Marshall admits that the downside of being a “spoiled child” and having his mother clean his room, was the opportunity for her to have access to his journal. Inside, Marshall says his mother read descriptive details of his experiences at Lenox Mall and Atlanta Pride.

“She basically made me confess,” he says. “You're going to pick something today. I need to know men or women today,” Marshall recalls his mother demanding.

“I told her men. And after that I was free,” he says. “They cried. You would've thought that I had died,” he says through laughter.

In a sense he had. The former closeted Marshall had to die in order for the man and the artist to be born. While the death of his assumed heterosexuality was a figurative one, two of his most loyal supporters, his sister, and mentor Charles Gregory, a longtime celebrity hairstylist to Tyler Perry, made their transition during a year of monumental loss.

“My sister was very supportive of me and would always come to my shows. She actually purchased work from me and always told me to keep going,” says Marshall.

And in a voice cadence reminiscent of Gregory, Marshall channels the flamboyance and motherly encouragement of his late mentor.

“You’re doing it. Oh, honey, you’re selling this work! You’re selling it, honey!”

“I Want To Be In Spaces”

Before the social unrest that occurred during the summer of 2020, Marshall intentionally steered clear of politics and religion publicly. But as his work occupied more spaces, it became clear that he needed to use his platform to give voice to social issues impacting the Black community and Black LGBTQ+ people.

“As an artist, you have a platform. So, I feel like we have some sort of responsibility to create or say something in your voice,” he says.

“We Must Have Justice,” a piece Marshall created using old newspaper articles and an industrial printer, speaks directly to the injustices Black people faced during the Civil Rights era through the present day. It’s one of several pieces that soared in popularity over the last year.

“With all the injustices going on, the killings and shootings and riots, I think that people really wanted to celebrate and support artists of color in any way that they could,” he says.

And making art that is accessible to the average person and not only wealthy art collectors is also a focus for Marshall.

“I try to price all of my work reasonably. Because for me as an artist, I want to be in spaces. I want to be in your home. I want to be in your office. I want to be in your clubhouse or your business because that is priceless. I want to work with real people. Real people have real jobs, real people have real bills,” he says.

Besides his art being accessible, Marshall says it's also important for him as an artist to be accessible beyond the social media realm—transforming likes and views into priceless personal interactions between the artist and consumer that enhance the overall experience.

“People have to fall in love with the artist,” says Marshall. “If people didn't really know who Basquiat was, they wouldn't be buying his work. If they didn't really like Beyonce, they’d be like, I mean, she's cool, but I don't really know her,” he says.

Marshall says his ability to tell a story not only through his art but through genuine conversations about his creations sets him apart from other artists.

“You have to talk to people. You have to get out to the crowd. You have to meet and mingle and let people know you are alive and tell them about the work and give them details and give them stories,” says Marshall.

“People have to fall in love with the artist,. If people didn’t really know who Basquiat was, they wouldn’t be buying his work. If they didn’t really like Beyonce, they’d be like, I mean, she’s cool, but I don’t really know her.”

For an artist who has future aspirations of owning galleries bearing his last name in cities across the country, two of his pieces have been chosen to be featured online by custom framing company Frame Bridge during the month of August, as he works to assemble the bricks to build his dream.

“Every year they choose 10 artists, and this year they've chosen me,” says Marshall. "They've chosen two of my pieces, one of them which happens to be the Black Lives Matter print. I'm excited!"

It’s the epitome of gay Black boy joy for an artist who thought the well was always dry for boys like him.

“Growing up, being called names, picked on, [being] Black, male, gay, all combined, you develop an unbreakable joy,” says Marshall.

“And that is why I know that my work shines so bright now because I've turned all that around and made it positive.”