Celebrating Pomo Afro Homos: Pioneers of Black Queer Theater

For decades, Black queer creatives have used the art of storytelling to empower themselves and others by telling boldly unique stories created specifically for the Black LBGTQ+ community. However, not very long ago, there was a dire need for Black queer representation, even more so than it is today. In response to that void, pioneering San Francisco based Black gay theater troupe the Postmodern African American Homosexuals (affectionately referred to as Pomo Afro Homos) dominated stages during the early 1990s with their mix of humor, heart, and transparency in the wake of the burgeoning HIV epidemic and ongoing racial disparities.

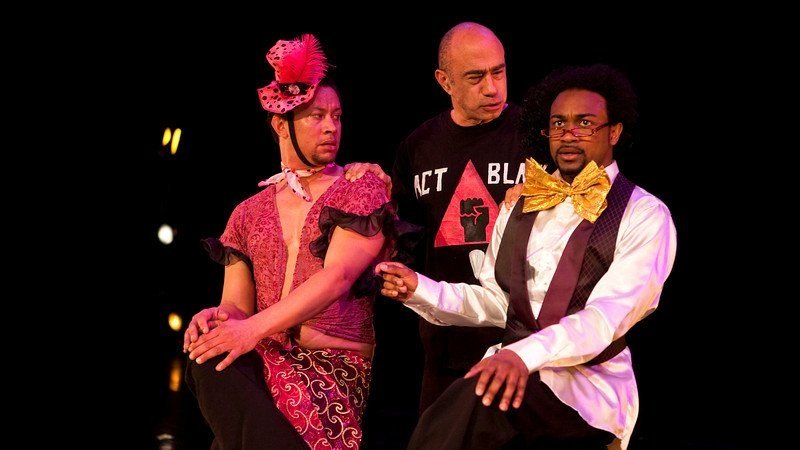

Born out of the need to see three-dimensional Black gay male characters in the world of theater, the Pomos consisted of choreographer/dancer Djola Branner, actor Brian Freeman, and actor/singer Eric Gupton. A fourth member, Marvin K. White, also shared his talented voice and charismatic presence to help bring their stories to life on stage. As the Pomos, these artists captivated audiences with their two-stage plays “Fierce Love: Stories From Black Gay Life” and “Dark Fruit” from 1990 until 1995. During his interview with The Reckoning, Djola Branner admits that when Brian Freeman first approached him about possibly forming a collective, he had no idea what to expect, although it was always clear that their stories had to focus on the Black gay male experience.

“I had not thought of myself as a theater artist at that point and (Freeman) said, ‘I wish we had a third person to enlist,’ and I suggested Eric Gupton who I was performing with as a dancer,” said Branner. “I also knew that he had a theater background. We sat down, the three of us, and within forty-five minutes we had outlined the first show Fierce Love; Stories From Black Gay Life.”

“All of us had been looking for three-dimensional Black gay men in media and on stages and we just couldn’t find them, so we’re going to do our own thing.”

- Djola Branner

The buzz surrounding the impending debut performance of “Fierce Love,” held at the iconic Josie’s Cabaret and Juice Joint in San Francisco, began to grow exponentially. And on the night of “Fierce Love's” inaugural performance, the Pomos were not initially prepared for the large audience that arrived to support the show. Still, in anticipation of the show’s debut, Branner reveals confidently that they knew what their mission was, and at that point, there was no turning back.

“We thought, you know, we’re gonna do this show. We’re gonna have a good time. We’re gonna tell these stories that really speak to our audience. All of us had been looking for three-dimensional Black gay men in media and on stages and we just couldn’t find them, so we’re going to do our own thing,” Branner said.

“Fierce Love’s” opening night saw a packed house at Josie’s with a line that wrapped around the block with tons of theatergoers, some who drove in from Oakland and were curious about a show regaling the triumphs and tragedies of current Black gay life. “Fierce Love” ran for two weeks at Josie’s, which catapulted the Pomos into high demand, leading to a nationwide tour that included Boston, New York, and Chicago. Their performances knew no limitations as far as venues were concerned. They would perform in spaces as small as college cafeterias and as large as Lincoln Center. Controversy soon followed.

Turbulent Times Ahead

According to Freeman, in 1991, The National Black Theater Festival in North Carolina banned the Pomos because of their unapologetic portrayal of Black queer expression. They also received dissent in 1993 ahead of their involvement with Anchorage, Alaska-based theater company Out North when then-mayor Tom Fink blocked advertisements for “Fierce Love” on their city buses. By telling their stories in the face of adversity, the Pomos often incorporated their challenges with discrimination into their shows.

After five years of creating and performing together, the Pomos went their separate ways in 1995. Branner continues to teach, write and perform, including a stage production celebrating the life and times of iconic singer Sylvester in “Mighty Real: A Tribute to Sylvester,” as well as “The House that Crack Built,” “cover” (a Samuel French finalist), “oranges & honey,” “Sweet Sadie” and “sash & trim.” Brian Freeman also continues to be an active force in theater. He directed a revival of “Fierce Love” in 2012. Marvin K. White went on to become a successful poet and theologian, currently leading a new generation as the Minister of Celebration at Glide Memorial Church in San Francisco. Eric Gupton continued working in theater and voiceover after breaking away from the Pomos, yet sadly passed away in 2003 from HIV-related complications.

“He was so out there in his personality, it was hard to take your eyes off him when he was onstage. He loved an audience, and it loved him. He was the one people always got crushes on. They’d send him flowers backstage.”

In an interview with SF Gate after his death, Brian Freeman said of Mr. Gupton, "He was so out there in his personality, it was hard to take your eyes off him when he was onstage. He loved an audience, and it loved him. He was the one people always got crushes on. They'd send him flowers backstage."

During their time together as a collective, the Pomos provided a huge chunk of unforgettable history that has been praised for decades after their first performance at Josie’s in 1991. It's work that Branner, who is now Director of Theater at George Mason University, believes is still relevant today.

“A theater company in New York, TOSOS, did a reading of “Dark Fruit,” maybe six months ago, and I was surprised how the work still resonates in 2021,” Branner said. “I think that it certainly laid the foundation for others. It created space for us all to understand that the stories that were being propagated in the popular media were not the only stories of America. Certainly, there are a lot of examples of that now, but there weren’t as many thirty years ago.”

“I think we were really in one of the first waves of theater artists doing that and I think that laid the foundation for a lot of the stuff we’re seeing now, which is great.”

Branner says he is honored to be included in the names of pioneering Black queer creatives such as renowned poet/storyteller Essex Hemphill and Marlon Riggs, with whom Branner appeared in the groundbreaking film “Tongues Untied” along with Freeman prior to the creation of the Pomos. In fact, “Fierce Love’s” title is inspired by a line in Essex Hemphill’s poem, Black Beans.

“I think we were really in one of the first waves of theater artists doing that and I think that laid the foundation for a lot of the stuff we’re seeing now, which is great. Culture has shifted, too. The conversation has shifted, the terminology has shifted. The idea of (being) gender nonconforming certainly existed thirty years ago, but there was a different language when we even talked about gender. I think all of those conversations and those works have helped provide more fluidity and essentially more honesty about who we are,” he said.

“Continue to create the work. Continue to ask questions to challenge the power in the room, whichever room you happen to be in. And by that I mean just speak your truth. And look towards other people who are doing it. You have a lot of folks who paved the way.”

- Djola Branner

As an instructor with an extensive wealth of knowledge to impart to future generations of storytellers, Branner requests that his students tell their stories with truth in one hand and compassion in the other, never shying away from naming the things that they’re afraid of. And as far as any queer creatives facing adversity today, he advises them to do the work anyway, especially finding a way to incorporate humor while discussing heavy topics.

“Continue to create the work. Continue to ask questions to challenge the power in the room, whichever room you happen to be in. And by that I mean just speak your truth. And look towards other people who are doing it. You have a lot of folks who paved the way,” Branner said.

Then, he cautions, “Now I’m not saying we should go out and create work just to make people comfortable. If that’s what you’re doing with your work, I don’t think that’s a good thing. But I think if you are committed to the truth in whatever you’re attempting to write or dramatize, and within that truth you find a joke,” he shrugs, then smiles; “good on you.”

Other Content You May Enjoy

Ben Robinson III is a writer from Philadelphia. Discovering his love for writing at a very early age Ben has written for both the stage and screen, self published multiple books and performed his poetry in various places around the country and internationally. Follow his journey on Instgram @bentheoutspoken or contact him at writer.benrobinson@gmail.com.