Exhuming Black Gay Artist Tré Johnson, 26 Years After His Death

“Exhume those bodies. Exhume those stories. The stories of the people who dreamed big and never saw those dreams to fruition. People who fell in love and lost.”

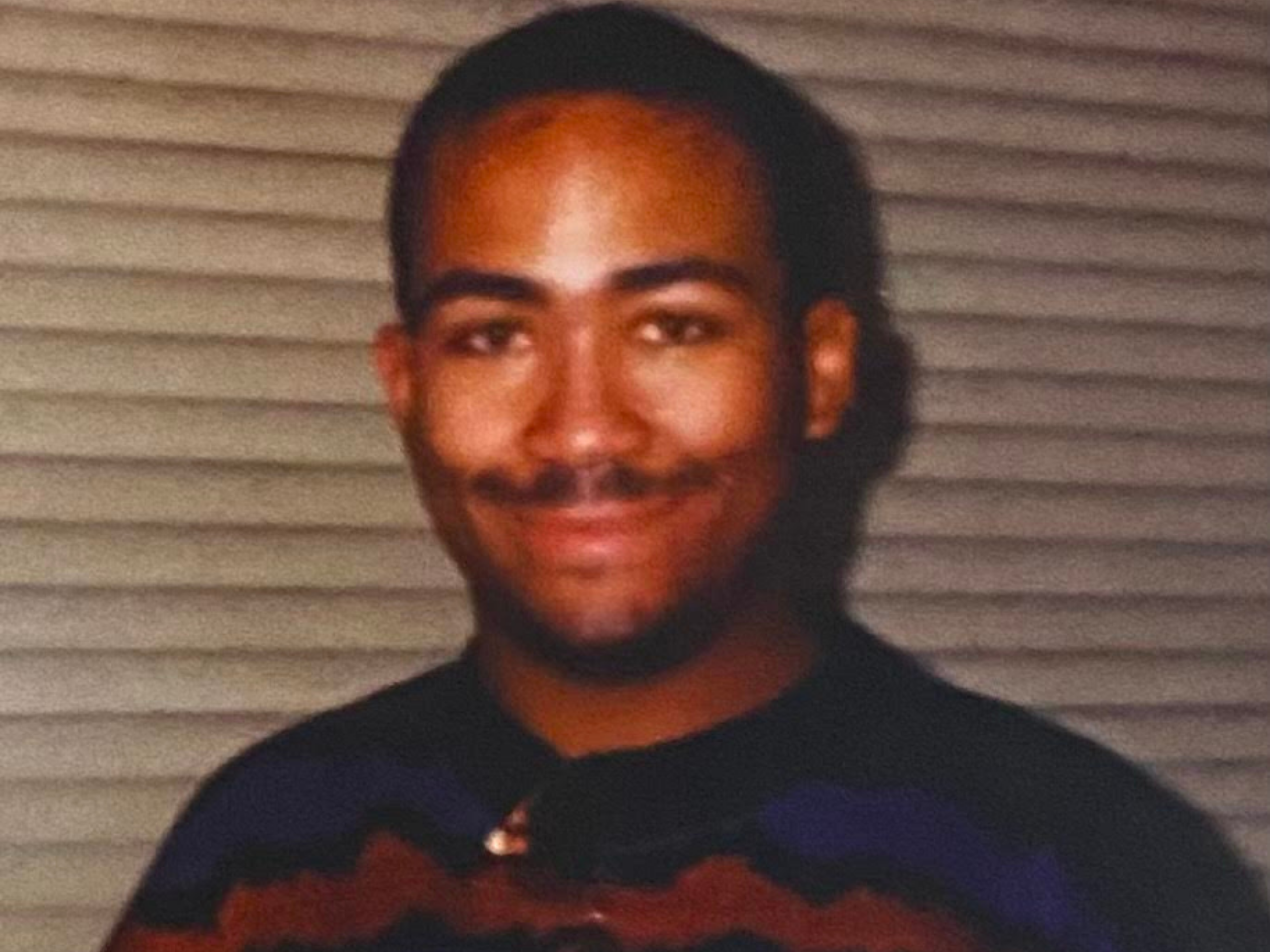

This April will mark the 26th anniversary of the death of R. Leigh Johnson, III, or Tré, as he was affectionately called by his family and those in Atlanta's burgeoning Black gay community of the early '90s. A talented poet, singer, and activist, Tré (as I will refer to him going forward) was a creative force whose light dimmed entirely too soon. Having moved to Atlanta a decade after his passing, I'd never heard his name mentioned in activist circles or read any of his poetry. I didn't know that he'd once walked the same streets as I did and made it possible for me to experience the liberation and freedom I now enjoy as an openly gay Black man.

On a cool day in January, I made a rare trip downtown to visit the LGBTQ archives at the Auburn Avenue Research Library. On a three-tiered cart to the right of a desk, in a dozen or so gray boxes, all neatly lined up in a row, was over 30 years of Atlanta Black LGBTQ+ history waiting for me. With my visit to the National Museum of African American Culture in D.C. still fresh on my mind, I unrealistically expected a similar experience. Despite this not being the case, what I found proved to be just as impactful and historically significant.

There he was, in black and white, his words leaping off the page, flaunting a smize that would make Tyra Banks envious, with a fierce-brimmed hat tilted to the side and a big hoop earring in his right ear. I was struck by his beauty and the urgency of his words. From the grave, 26 years after his death, Tré demanded my attention and refused to let go. I had to exhume his story.

Born in Atlanta on July 21, 1970, to musician Roy Lee Johnson Jr. and traffic inspector Juanita Moss (who passed away in 2015), Tré was the youngest of three children and the only boy to sisters Twila and Monica, the oldest. Raised in a loving home in Southwest Atlanta, Monica tells The Reckoning that she remembers her brother as a mama's boy who lived at home and made it a priority to take care of his mother, a devout Jehovah's Witness, and his sisters. As a feminine, presenting gay man, Monica admits the family was often concerned about how others would receive Tré.

“Knowing that he was different from just your regular brother—we were always worried about whether or not people would really accept him as he was,” Monica said. “That was truly important for all of us because he was kind. He was gentle. He would do anything that people asked.”

“Knowing that he was different from just your regular brother—we were always worried about whether or not people would really accept him as he was. That was truly important for all of us because he was kind. He was gentle. He would do anything that people asked.”

A 1988 graduate of the Northside High School of Performing Arts, Tré traveled and performed internationally with the school's highly regarded Northside Tour Show. At Northside, a young Miko Evans, Founder and Executive Producer of Meak Productions, first encountered the man he calls a pioneer of the golden era of Atlanta's Black gay movement.

“I always tell people Tré was the one that introduced me. I didn't even know there was an LGBTQ community,” Evans says, of his friend whom he fondly recalls planning Labor Day activities with in 1993, before the existence of “In The Life Atlanta,” the longtime organizational arm of Atlanta Black Pride.

Evans tells The Reckoning that in 1991, Tré disclosed that he was living with HIV, a fact about his life that he would consistently address through his writing and community work despite the HIV stigma and paranoia at the time.

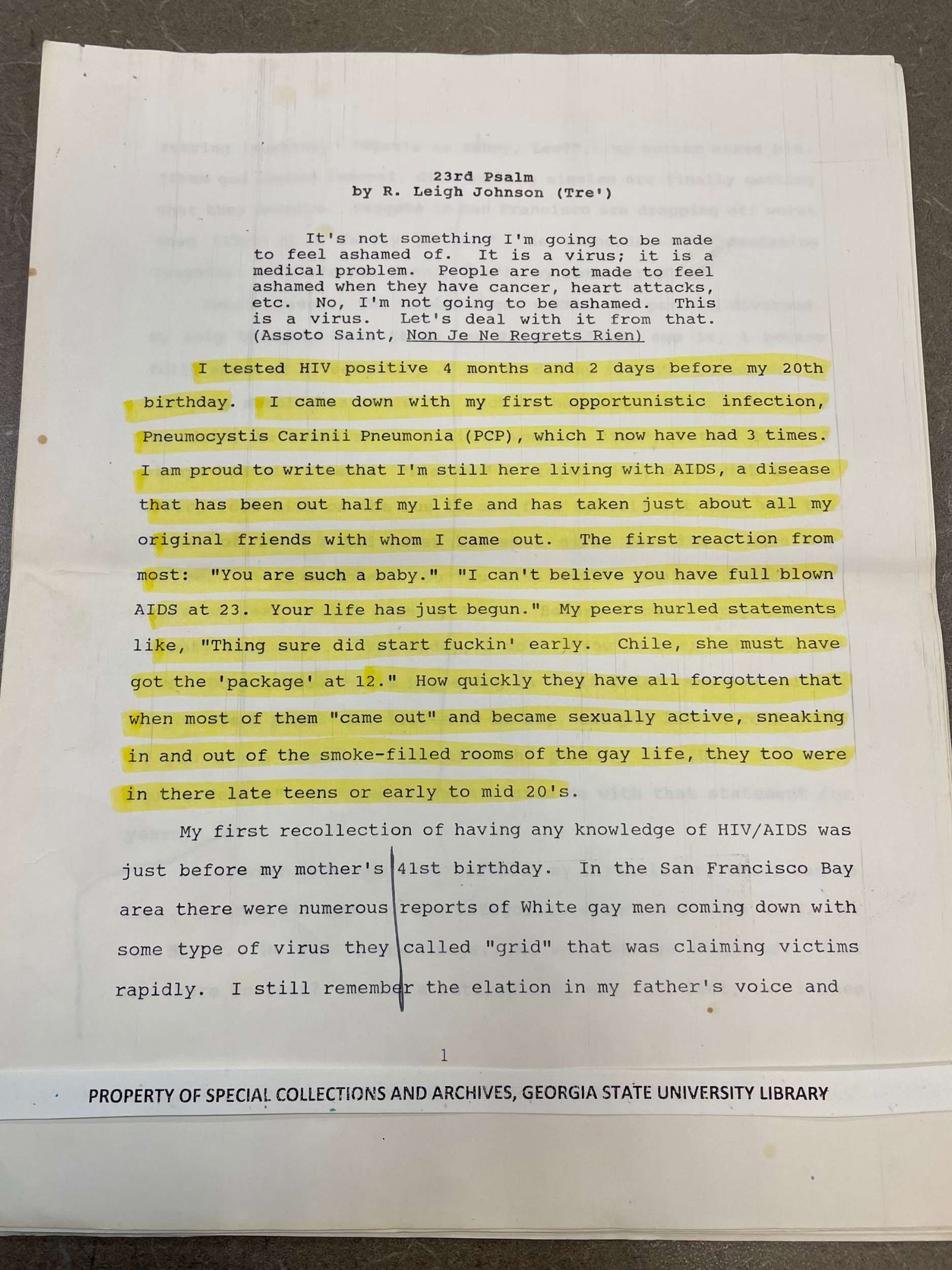

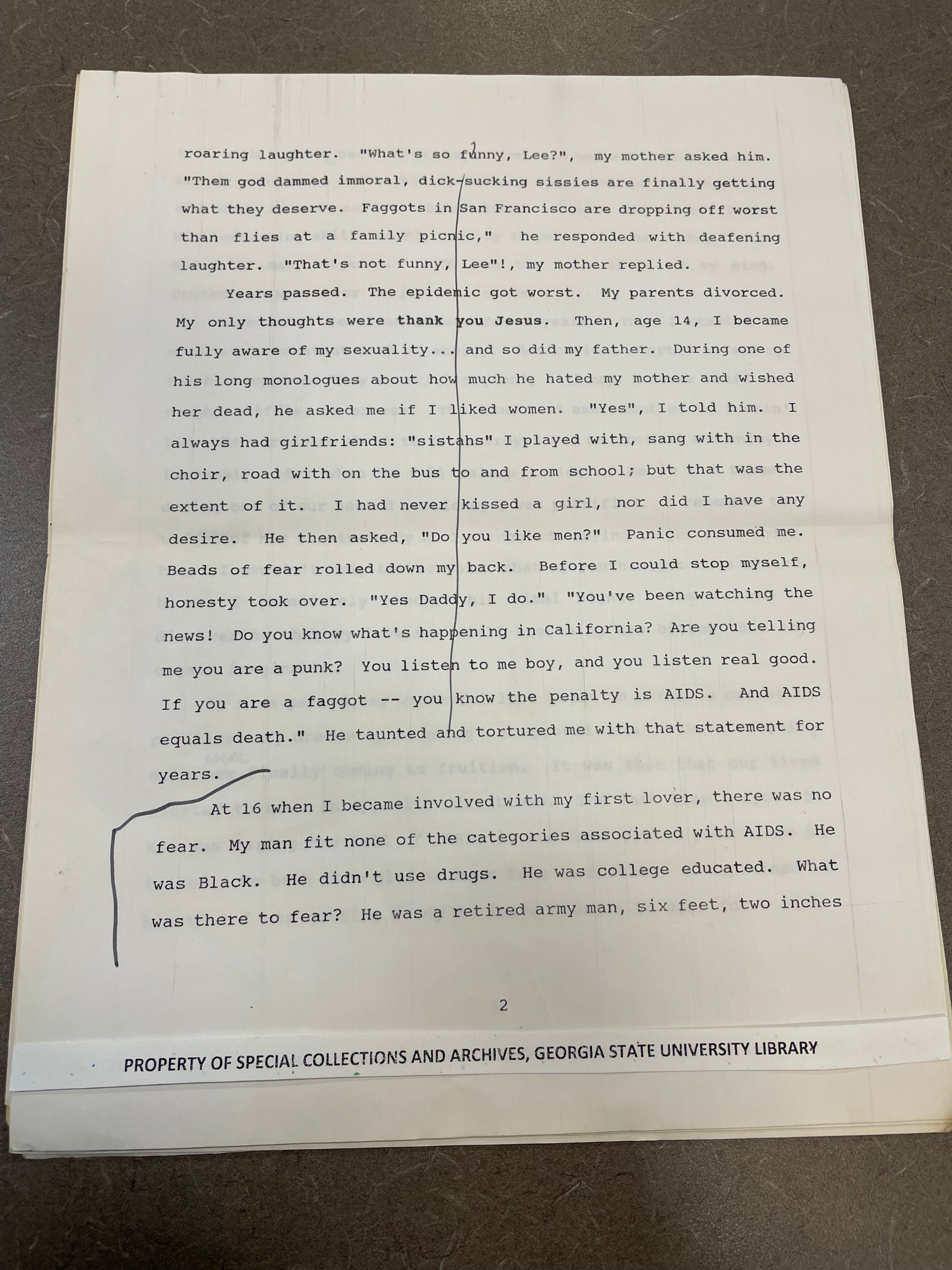

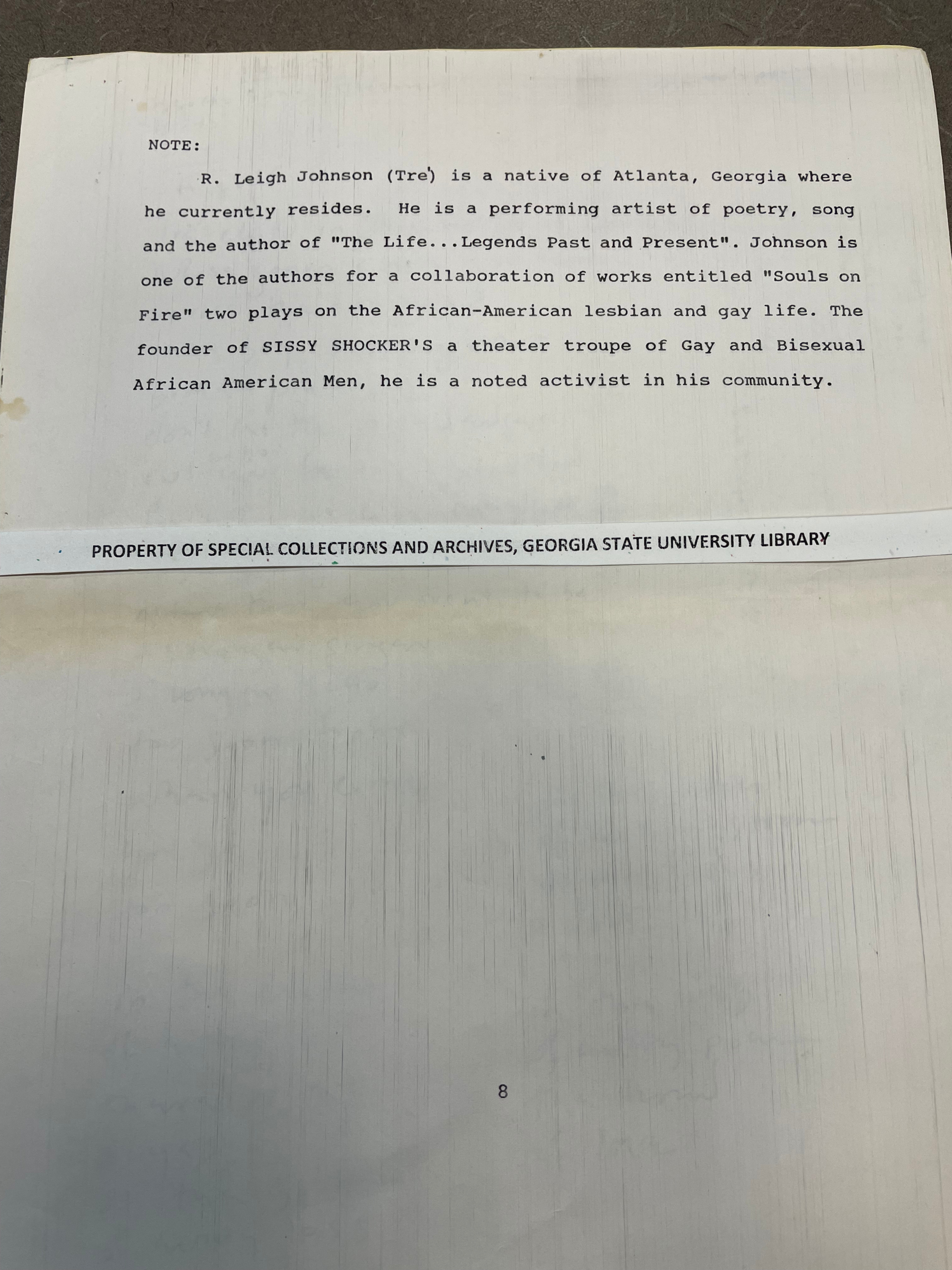

“My initial plan after finding out that I was infected with the AIDS virus was to go to Honolulu to die peacefully and gracefully," Tré wrote in the '23rd Psalm,' a paper reflecting on the early days following his diagnosis now housed in Special Collections and Archives at Georgia State University Library.

23rd Psalm

by R. Leigh Johnson (Tre’)

“Hawaii was a place that I have always wanted to visit; I could live with my cousin and her family. I went through a series of major changes: sleep was a stranger; eating was out of the question. All I did for a week was cry, scream, and wait for death. I became very dependent on nerve medication, sleeping pills, and alcohol. I wanted to remain as high as I could for the rest of my life, however long that was.”

"During the early stages, there was not enough help for our community, and AIDS was still a crisis, especially down here in the South," Evans said. "Through activism, he channeled his frustration, disappointments, pain, and hurt as it related to his struggle to deal with HIV."

“During the early stages there was not enough help for our community and AIDS was still a crisis, especially down here in the South. Through activism, he channeled his frustration, disappointments, pain, and hurt as it related to his struggle to deal with HIV.”

Evans says it was through Tré that he met Duncan Teague (now Rev. Duncan Teague, Senior Pastor of Abundant LUUv Church) and Craig Washington. Both men are at the epicenter of Atlanta's Black LGBTQ+ movement and were deeply connected to Tré while alive.

"Tré was fierce. That's the word—fierce-in ways that I wasn't back then or in a different way than I was, and rightly so. I didn't have HIV," said Teague.

When it comes to the lives of Black LGBTQ+ public figures, the continuation of their stories into future generations often relies heavily on oral history. Over time, memories can fade, both intentionally and unintentionally.

“During that time, there were no cell phones. There was no digital media. We’re talking about the era of pagers,” Evans said. "[People ask] how come somebody didn’t document history in the making as it was happening? One of the elders told me, he said, ‘Miko, we were too busy just trying to stay alive.’”

“One of my survival mechanisms was trying not to remember all the details, which is not fair to history because it just kept happening,” Teague said. “Like Omicron, there is hardly a person in my little congregation for whom it hasn't affected. And that's how HIV was back in the day. They died. They didn’t go on a respirator and come back out. That didn’t happen until after 96,” Teague adds before allowing his mind to wander back to the devastating time when Black gay men were here one day and gone the next.

“It was the guy who was working at the desk at AID Atlanta. It was two cute boys who were volunteers. It was your friends. It was your friend's lover. It was Tré.”

Tré: The Artist

Teague tells The Reckoning that Tré’s age at the time of his passing in April 1996, at 25, was one of several reasons that intensified the community’s grief.

“He was not happy about dying. He was angry about it. And he should have been because he was going to do it,” Teague said. “He made alliances and went to be with Assotto Saint in New York. There are photographs of Tré with Assotto. So Tré wanted in.”

Assotto Saint, another brilliant and trailblazing Black gay poet, playwright, and publisher who also succumbed to HIV-related complications in 1994, two years before Tré, was someone he considered a mentor. The two artists were connected by Franklin Abbott, a gay Atlanta psychotherapist and founding member of the Radical Faeries, as HIV had begun to take its toll on both men.

“I think they identified with each other because they were both struggling,” Abbott says. “They were both sick. They were in that sick phase of HIV. And you can see that in the photograph. You know, both of them were at one time much healthier and more vibrant than in that little Polaroid.”

“He was not happy about dying. He was angry about it. And he should have been because he was going to do it.”

Teague, a founding member of “Adodi Muse: A Gay Negro Ensemble,” also recalls a much healthier and artistically driven Tré.

“When we formed “Adodi Muse,” he also formed “Sissy Shockers," Teague said. "And notice the difference in the names: “Adodi Muse, A Gay Negro Ensemble” and “Sissy Shockers.” Their writing was more in your face."

Terence Jackson, an artist and curator of U Space Gallery was a member of “Sissy Shockers” and one of Tré’s closest friends. The two met in 1991 at the now-defunct Atlanta Men’s Center following one of Jackson's performances. The inseparable duo would go on to perform together at the Out Proud Theater, which has also since closed.

"After I finished, he was one of the people that came up to me and said, 'Oh, we have to work together,'" Jackson recalls. "We just had this really great bond, and we called each other brother from the moment we saw each other."

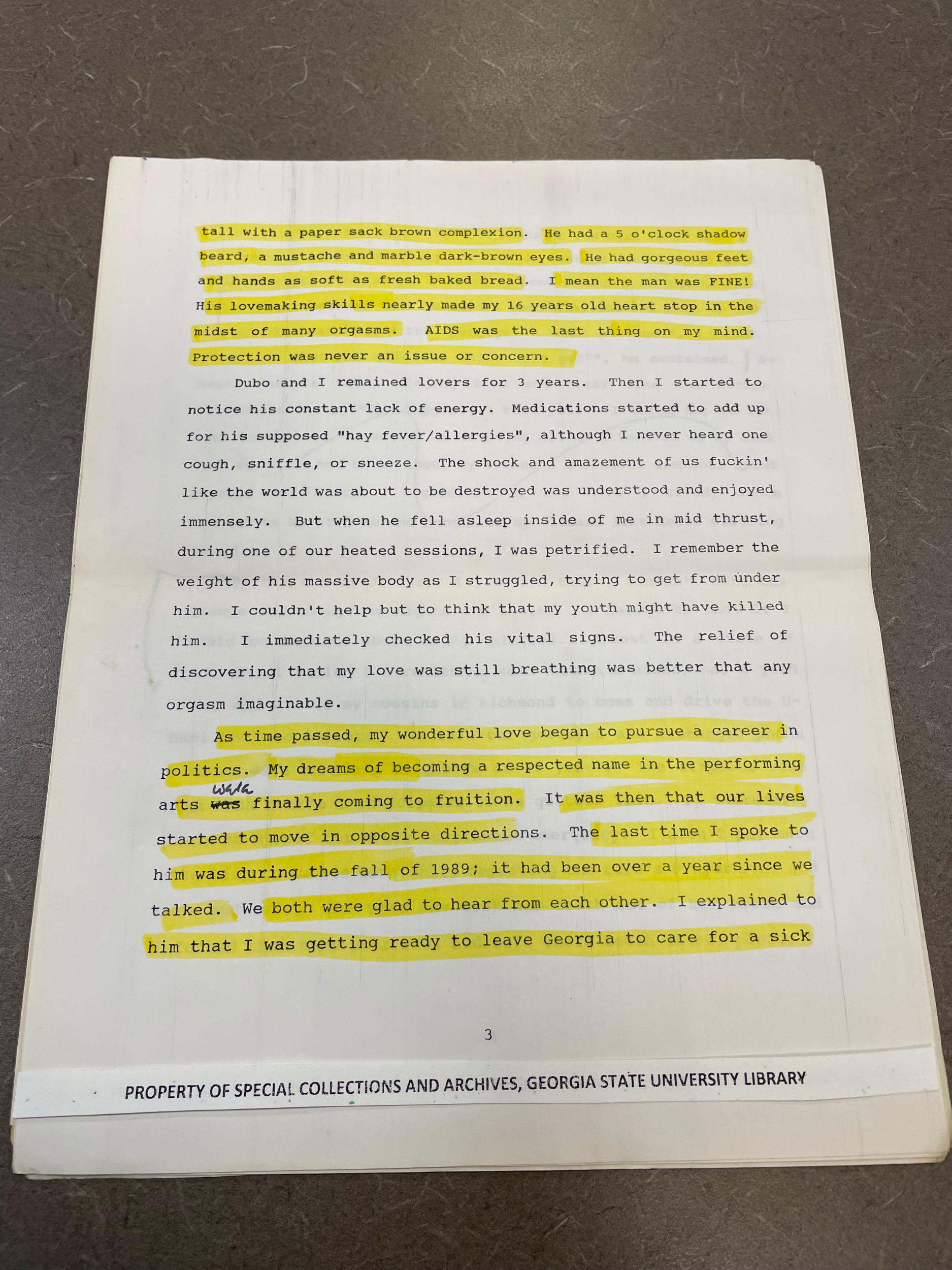

Jackson tells The Reckoning that much of the content Tré created for the shows they performed together revolved around the moment he realized he'd acquired HIV from a man he deeply loved. A fact that didn't seem to matter to some Black gay men who, upon learning his status, were almost as cruel to Tré as the virus attacking his T-cells.

"My peers hurled statements like, 'Thing sure did start fuckin early. Chile, she must have got the 'package' at 12,'" Tré wrote. "How quickly they have all forgotten that when most of them "came out" and became sexually active, sneaking in and out of the smoke-filled rooms of the gay life, they too were in their late teens or early to mid-20s."

Although he was dying, Tré never denied himself the experience of giving and receiving pleasure; however, it presented itself, which he wrote about often. He used the power of his pen to plan his funeral, which included a list of people who were forbidden to speak. Craig Washington was on that list.

Running Out Of Time

A New York City transplant, Washington, moved to Atlanta in 1992 with his then partner, Lenny. He and Tré's paths crossed during a reading for Black gay poets at Charis Books shortly after his arrival.

"I think I'd been in Atlanta, maybe three months. And so I really didn't know any of the kids, and it was through Tré that I eventually met most of them. We took an instant liking to each other and quickly formed a bond," said Washington, who was intentional about finding his tribe of artists, thought leaders, and activists in Atlanta.

But as quickly as their friendship began, it would end within a couple of years.

“Tré and I had a wreck which we never recovered from,” he said. “I remember that night so well. It had been at least a year before Tré passed when our friendship had pretty much ended.”

Tré invited Washington to read his writing on a program for Black gay poets at First Metropolitan Community Church. Tré was also scheduled to perform. Washington says he extended an invitation to Tré to return to the home he shared with his deeply closeted partner afterward under one condition.

"I said, Tré, if you don't mind, Lenny is still pretty closeted. He would like it if you didn't make any mention about us being a couple, particularly in front of his friends. Tré took it to mean that I was asking him to be closeted himself," said Washington.

"He started mocking a butch affectation. 'Okay, man, you want me to do that?' I said, Tré, chill. That's not what I'm saying," recalls Washington. "But in hindsight, I think that triggered something for him, particularly as a young fem-identified Black queer man. He probably didn't have the wherewithal to make the distinction."

Washington tells The Reckoning that he and Tré were never the same.

“He saw me as another Black gay man who was mean to him. I apologized, but he didn’t receive it.”

The next time the estranged friends would share space would be during a "Safe, Sexy, and Proud" meeting organized by AID Atlanta for Black gay men to establish community and share resources while fighting HIV.

"AID Atlanta, by then, still had a lot of unchecked institutional racism," said Washington. "So they hired me. Even though AID Atlanta, by the nineties, was certainly serving Black men, it was largely distrusted. Tré was there, and it meant a lot to me that he showed up. But by then, he was sick."

Tré was running out of time.

"I'm almost sure the last time I saw him was on his couch in his house with a big floppy hat on, looking fabulous, and just kind of letting people have it," Jackson remembers.

In the last few months of his life, Tré alternated between his home in East Atlanta and as a patient at Emory Crawford Long Hospital.

"He was having some physical issues and was in and out of the hospital, but that final time you could tell that his memory was being affected," said Monica, who, along with Tré and his other siblings, somehow managed to find humor amid the devastation.

"He thought he was telling us off in a letter, but it really didn't make any sense," Monica said. "He thought he could be the boss of my sister and me. I'm the oldest, and he was the baby. That's a really good memory that we still have and laugh about because he really thought he was doing something."

“I watched Tré, and at the very end, his eyes were wide open. It was like a light was coming out of his eyes. They opened really wide, and he had this beaming smile on his face and then he took his last breath.”

Another friend, Ricky Wilson, would often sit with Tré at the hospital and was trusted by his mother to care for him in her absence when she attended service at The Kingdom Hall. He was with Tré the morning he died.

"Tré made the decision that he was going to come off of his medication and just go on," said Wilson. "I took turns with his mother. We were in the room the day he died. The nurse came in, took his vitals, and said he was passing. I watched Tré, and at the very end, his eyes were wide open. It was like a light was coming out of his eyes. They opened really wide, and he had this beaming smile on his face, and then he took his last breath."

The Homegoing

Monica remembers her brother being at peace. She said he was ready to go.

“He had already planned his own funeral. He told us what to wear. It was all written out. He had made arrangements about where it was going to be. So when it happened, all we had to do was follow what he asked us to do. I thought that was such a brave thing for such a young guy at the time to do,” she said.

There were two services for Tré, a traditional Jehovah’s Witness funeral reflecting his mother’s faith and a community memorial service that reflected the totality of his identity as a Black gay artist and activist. The traditional service received mixed reactions from Tré’s queer friends who were in attendance.

“It was orchestrated for somebody other than us,” said Teague. “It was not a Black gay funeral. It was a funeral for a Jehovah's Witness woman who lost her son and his family who were there, and they kept it in line with that. We knew we were gonna do for Tré what we needed to do.”

“It was orchestrated for somebody other than us. It was not a Black gay funeral. It was a funeral for a Jehovah’s Witness woman who lost her son and his family who were there, and they kept it in line with that. We knew we were gonna do for Tré what we needed to do.”

"This is what I'm sure of; Juanita Moss loved her son," said Wilson. "She was there. She might have had some issues with him being gay. I'm not sure. I never heard any disparaging remarks."

Before he died, Tré was sure that his mother loved him unconditionally.

“She is the woman who told me, 'I don’t care if you are a Black gay man with AIDS. You are, first and foremost, my son, my baby, and mama’s gonna love you as long as she can,'" he wrote.

As one of the organizers of Tré's community memorial service, Teague says Tré had given explicit instructions regarding who was not allowed to speak at his celebration of life.

“He made that list very clear to me. And at the meeting to plan his community memorial service, those of us who knew had to relay that information,” Teague said.

“Duncan [Teague] asked me to meet him in Little Five Points, two blocks away from the very spot where I first met Tré,” said Washington. “And it was to tell me that I was barred from speaking at Tré’s funeral. I was on the list. I was already mad at Tré because he wouldn't forgive me. And then, he dies, which means we don't get to have that conversation. And then posthumously, he threw me shade,” Washington says through laughter.

“I have survived and passed some of life’s most challenging tests. I have dedicated my life to what I love most: performing, entertaining, and educating society about men who love men. I hold my head up high and represent a certain strength and vitality in the community I so love.”

In 25 short years, Tré left this world, having lived as much life as he could.

“I have survived and passed some of life’s most challenging tests,” he wrote. “I have dedicated my life to what I love most: performing, entertaining, and educating society about men who love men. I hold my head up high and represent a certain strength and vitality in the community I so love. And, most of all, I have found the soul mate for whom I’ve searched for many years! He is a man who makes me happy and has vowed to love me as much as I love him… and to love me to the end.”

“There are a lot of unsung heroes that never get mentioned when we talk about Atlanta's Black gay history,” said Evans. “Some are still alive, and some have passed on that made a significant impact in the success of Atlanta's Black gay movement, and Tré was one of them.”

(Cover image of R. Leigh (Tré) Johnson courtesy of the Johnson Family)