Going It Alone: Gay Black Men Take on Single Fatherhood with Purpose

From pampers and potties to pimples and proms, anyone who’s raised another human will tell you there are a lot of “Ps” that come along with parenting. Among the most useful “P," many would agree, is a partner—someone to nudge at night for their turn to bottle feed, take on soccer practice duties or handle any of the other million tasks that come with raising a child to adulthood.

And yet for Black gay men, the dearth of marriage-worthy partners has put the dream of a nuclear family far out of reach.

That’s changing.

This spring, millions of men will celebrate Father’s Day as single dads, part of a trend that has exploded over the past few decades. Among them are an increasingly visible number of gay men and male figures, many of them casting aside traditional timelines and methods of creating their family and redefining when and how one should become a parent.

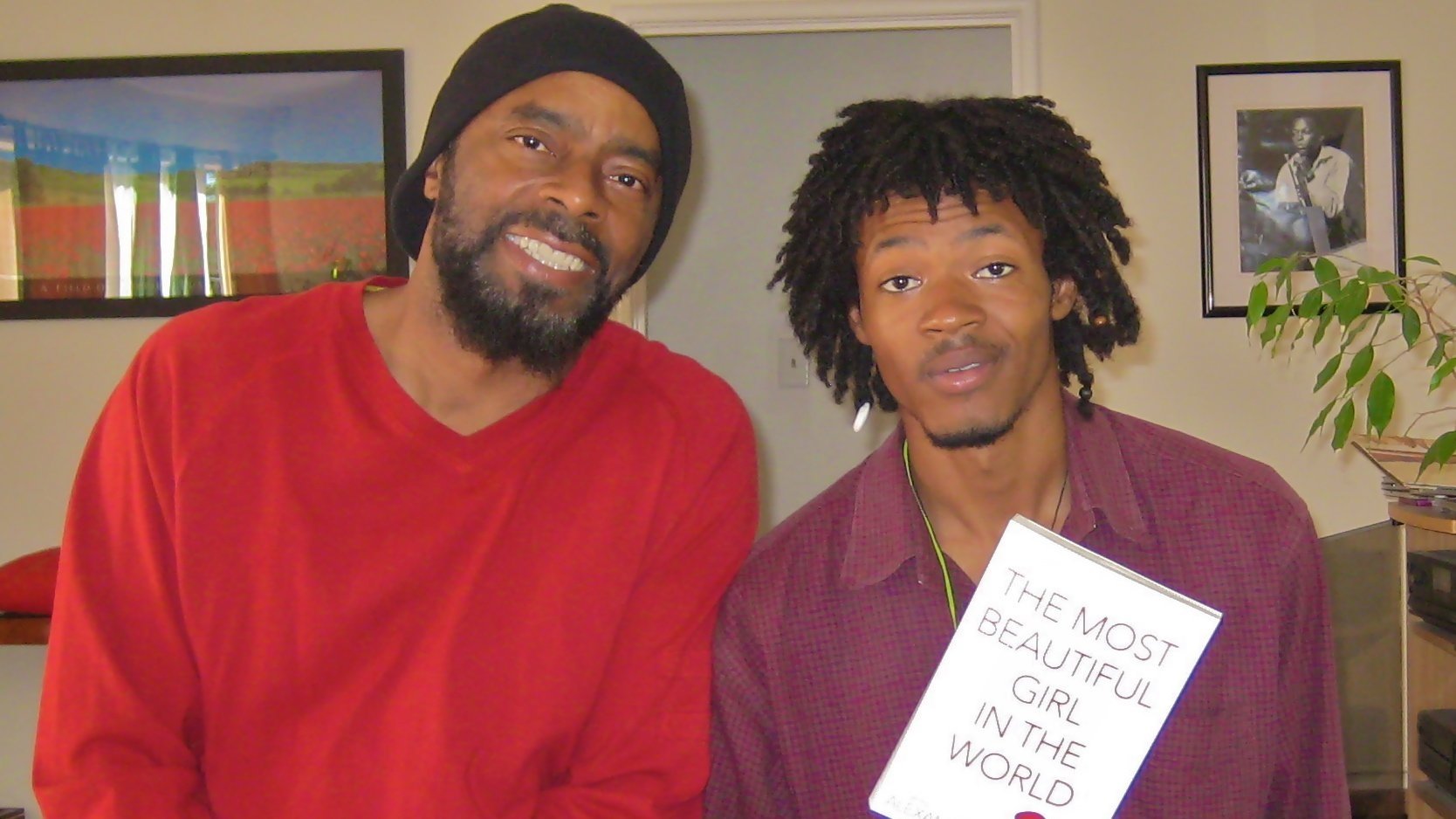

They’re men like Alexander Langford, an Atlanta-based author and baby boomer who, at age 40, felt the importance of raising a Black child in America mattered more than whether he had a mate along for the ride. More than two decades later, adopted son Xee Langford is a thriving musician.

“A lot of people are intimidated by the prospect of doing it solo,” the elder Langford says. “I wish I could counter that perception. It’s not impossible.”

“A lot of people are intimidated by the prospect of doing it solo. I wish I could counter that perception. It’s not impossible.”

- Alexander Langford

A world away, New York City storyteller Nathan Yungerberg has taken on single fatherhood not once but twice, after learning his soon-to-be adopted daughter had a sibling.

“I found out a year and a half later that the birth mother and birth father were having another baby,” says Yungerberg, who didn’t want the children growing up apart. “After a lot of back and forth and a near nervous breakdown, I decided to welcome him into our home as well.”

Both men point to sacrifices—tighter budgets, teen growing pains, sleepless nights—that come with choosing to go it alone. But they also point to the joys, among them raising a boy to manhood and empowering a Black child in a world that doesn’t always show them their value.

“I don’t really see there being any distinction between having any combination of parents,” Langford says. “As long as there’s security, none of that other stuff should matter.”

The Face of Modern Parenthood

One-in-four American parents living with a child are unmarried in 2022, a number that increasingly includes single men. That number has been on the rise for decades, with the type and age of men entering single fatherhood also evolving.

According to Census data, in 2021, 2 million men lived without a spouse or partner and their minor children. That means 29 percent of single parents are fathers—up drastically from years past.

Among children raised by single parents, some 60,000+ are estimated to be raised in homes headed by a single gay man, though researchers say numbers are limited by data collection methods.

For adults LGBTQ+ and otherwise, experts say rises in single parenthood align with increased divorce rates amid shifting cultural beliefs surrounding the centrality of marriage to parenting.

Yungerberg always envisioned a husband in his parenthood fantasy. But as he entered middle age, the busy creative found himself single and increasingly worried the window for fatherhood was shrinking.

“When I got to my late 40s I just thought God, I’m gonna be 50 really soon and time is just moving so fast,” says Yungerberg, who is finalizing the adoption of a 2-year-old girl and a 17-month-old boy. “I was like, screw it, I’m gonna do it!”

“When I got to my late 40s I just thought God, I’m gonna be 50 really soon and time is just moving so fast. I was like, screw it, I’m gonna do it!”

- Nathan Yungerberg

While his path to parenthood may be unique, Yungerberg’s status as a single adoptive father isn’t: Adoption statistics show that while women may comprise the largest portion of adoptive parents, men are more than twice as likely to adopt. But single fathers can face surprising social stigmas. Those can range from discomfort and isolation in parent circles dominated by mothers, as well as a pervasive societal message that casts fathers as “backup parents” rather than capable caretakers. Yungerberg takes other people’s reactions to his family in stride.

“I’m a Black gay man, 50 years old. I probably should have died a long time ago,” he says. “And I’m still standing. I just know that we’ll be fine.”

Ending Generational Traumas

In the ‘90s, Alexander Langford, then living in Oakland, Cali., realized he had a home, a great career, and financial stability—but no family of his own.

“My siblings had had children and relationships and what not and I just felt the need to create a forever bond, family, relationship with someone I could help,” he says. “I was ready.”

He was also single. But he wasn’t willing to let that stop him. A school teacher at the time, he had years of experience with children under his belt.

“I also at the time had a circle of other single fathers, some adoptive and some not,” he says. “We would meet once a month or so in support and brotherhood and talk about challenges and rewards and benefits.”

Certain he could handle being a dad, Langford went to a private adoption agency and began the lengthy process of qualifying to adopt, including a 10-week class, certification, and an extensive background check. Finally, he had to choose a child. Langford says he looked at just one picture.

“I still have the picture in my files. It was a black-and-white picture of him and he had these huge eyes,” Langford says, remembering the first time he saw Xee. “I just saw the soul in his eyes that told me that I should go to the next step.”

But the little boy he had set his eyes on was three years old—far older than the newborns many adoptive parents hope to snag. Langford wasn’t dissuaded. For one, he’d done enough diaper duty as an uncle and welcomed a youngster who was potty trained. And for two, his goal was bigger than pushing a stroller.

“I wanted to raise a Black child,” says Langford, whose own parents separated when he was very young. “I knew that I was going to stand by my son no matter what. I didn’t want to repeat that generational trauma of having the fatherless son syndrome.”

“I wanted to raise a Black child. I knew that I was going to stand by my son no matter what. I didn’t want to repeat that generational trauma of having the fatherless son syndrome.”

- Alexander Langford

Next followed months of visits designed to let the potential father and son feel each other out. Then one day, it happened.

“After about six months he called me dad once,” Langford says. “It was beautiful. It was natural. It was organic. And that was the beginning.”

Over the decades, Lanford says he has experienced all the ups and downs parenting entails, from the rebellious teen years to the isolating empty nest phase. Through it all, he says the experience has been surprisingly smooth and rewarding.

Nowadays, Langford and Xee can be spotted in photos on Langford’s Facebook timeline, both bearded and bespectacled, their status as adoptive rather than biological father and son hard to discern.

“The adoption class that I took in Oakland warned you about some of the possible pitfalls and we had one or two of them,” he says. “We navigated the problems and we’re standing tall together.”

“Screw It, I’m Gonna Do It!”

On a recent morning, Nathan Yungerberg found himself navigating a battle familiar to many parents: trying to wrangle wiggling, whining, uncooperative toddlers into their clothes and off to daycare on time. Just when he was reaching his mental breaking point, Yungerberg’s son started one of those random conversations toddlers are so good for.

“I thought, how did I get so lucky to get two beautiful children,” he says. “Ninety-nine percent of parenting can be pure hell. And then there’s that one percent of magic moments that just soothe your soul.”

Yungerberg had never intended to be a single father. But when he found himself nearing the half-century mark with no spouse or offspring, he began to feel he was running out of time to start a family.

“The idea of waking up when I’m 60 and doing it was like, no,” he says. “I still have a lot of energy left in me, so if I’m gonna do it, I’d better do it now.”

He began making changes in his life, toning down a busy social life and taking his health more seriously. He started New York’s foster to adopt program in June 2019, but soon learned not everyone was supportive.

“I told 10 people I was gonna do this. I had maybe one person who was like you’re gonna be a great dad,” says Yungerberg, himself an adoptee who ignored the critics. “You just really need to do what you think is best for you.”

“I told 10 people I was gonna do this. I had maybe one person who was like you’re gonna be a great dad. You just really need to do what you think is best for you.”

- Nathan Yungerberg

Yungerberg welcomed his daughter Fyre, now 2, in July 2019. Just over a year later, he says he got the news that Fyre’s parents were expecting another child, Fyre’s first whole sibling.

Yungerberg says he had to dig down deep to decide what to do. In the end, he welcomed Fyre’s younger brother in 2020.

“I know the kind of identity crisis that is inherent with the reality of being an adoptee,” he says. “I thought it’s gonna be an extreme sacrifice, but one that is worth it.”

Yungerberg’s life changed completely, he says. Weekly visits to trendy New York theater shows were replaced by late-night bottle feeding sessions. His work schedule now contends with getting the kids to daycare on time. And finding time for things like dating?

“I’m just trying to get through the day,” he says with a chuckle. “I don’t have a lot of bandwidth.”

Yungerberg says there are times when it’s challenging and even overwhelming. But the “right ons” and other encouragement he gets when people see him out and about with his kids make it all worth it.

“People are just excited to see men responsible for children,” he says. “It feels really good.”

Dionne Walker-Bing is an Atlanta-based reporter with over a decade of experience. Walker offers a distinct voice and unique skill for capturing the stories of diverse communities, perfected while writing for The Associated Press, The Capital-Gazette (Annapolis), and a variety of other daily publications throughout the Southeast. When she’s not writing features, Walker is busy traveling, crafting, or perfecting her vinyasa yoga skills.