Norris B. Herndon Remains the Black Gay Millionaire ‘Nobody Knows’

The outlook from the Herndon Home shifts dramatically throughout the day. Two blocks to the east, the morning sun shines on the intergalactic-looking Mercedes-Benz Stadium, a $33 million pedestrian bridge, freshly painted bicycle lanes, and other indicators that the development and displacement that have remade much of Atlanta have reached the Vine City neighborhood.

After the sun hovers above the Herndon Home and glides one block west, its rays turn harsher as they cast onto Herndon Stadium. Once the site of HBCU Classic football games and gold-medal matches in the 1996 Atlanta Olympics, Herndon Stadium is now an urban ruin—gated up, overgrown, and visited only by graffiti artists, adventurous youth, and adults without housing.

Listen to Ryan Lee Discuss Norris Herndon On I SEE U with Eddie Robinson

Pressed between these two concentrations of Atlanta’s history and future, the former residence of the family that bankrolled the earliest days and mightiest era in the struggle for Black equality faces an uncertain fate. The Herndon Home might emerge from the imminent gentrification with a sparkle that befits the plot of land it rests on, Diamond Hill; or it could crumble into ignominy like the once-famed Grace Towns Hamilton Home across the street, and the former Morris Brown College classrooms across the next street.

There is almost no one working to ensure the 111-year-old mansion will have a place in the new Vine City. Having been benefactors of their race and the embodiment of Black financial empowerment, there may soon be no home for the legacies of Atlanta’s first Black millionaire and his homosexual son.

Father, Son & The Meaning of Manhood

Norris Bumstead Herndon grew up in a shadow as broad as Georgia. Yet he could only live up to his father and society’s expectations by shrinking himself.

“Norris was a young man coming of age and struggling with his homosexual identity,” historian Carole Merritt wrote in her 2002 biography, “The Herndons: An Atlanta Family.”

“With a father who insisted upon a straight and narrow course and in an early 20th-century society that had no tolerance for what it considered deviant, Norris would have to deny himself. He would assume a compromised selfhood, his sexuality arrested, denied, or expressed in secret.”

Norris’s father, Alonzo Franklin Herndon, was a man of gargantuan lore. Born into bondage as the son of an enslaved mother and her white captor in 1858, Alonzo would go from slavery as a toddler and a childhood of sharecropping, to dying as one the richest Black men in America and leaving behind a company that exists in 2021. Uneducated but ambitious, he moved from Social Circle, Ga., to Atlanta in his early twenties and learned to cut hair, eventually owning a chain of barbershops that brought him into proximity with Atlanta’s powerful elites.

His Crystal Palace on Peachtree Street was chandelier-lit with porcelain and brass fixtures, nickel chairs with Spanish leather, French beveled mirrors, and white marble walls. Even though he could not enter through the front door of the segregated barbershop he owned, Alonzo ear-hustled knowledge that he would parlay into real estate investments, then used those profits to buy an entity he would convert into the Atlanta Life Insurance Company.

Alonzo was high-yellow enough to pass for white, but his commitment to negro advancement was as deep as his pockets. He not only attended and financially seeded the formation of the Niagara Movement, which would evolve into the NAACP, but he brought his young son with him—7-year-old Norris posing for iconic pictures from the 1905 gathering alongside historical giants like John Hope and W.E.B. Dubois.

“The significant organizations we have today such as the NAACP, the Urban League, Tuskegee University—all of those institutions have their roots with Alonzo Herndon and his son Norris Herndon and the Atlanta Life Insurance Company,” Roosevelt Giles, current board president of Atlanta Life said in an online presentation in 2020.

From his mother Adrienne—who was equally devoted to Black civil rights, to the point she quit working as a professional actress rather than pretend she was white—Norris inherited a passion for arts and theater. The immaculate, 15-bedroom Herndon Home, located at 587 University Place NW, was entirely Adrienne’s artistic vision, though she was struck with a rare illness and died just before its completion in 1910 when Norris was 12.

Alonzo and Norris represented starkly different eras of Black masculinity, and the father soon worried his son prioritized leisure over industriousness, and artistry over piety. When reading correspondence between the two men while interning at the Herndon Home during college, Pamela Flores sensed them using a code to conceal topics that were unmentionable in that era.

“‘Frivolous’ was the word Alonzo would use when he would write Norris at Harvard,” says Flores, a Vine City resident, and historian who researched the Herndons’ conflicting notions of manhood.

“You don’t come back to Atlanta with those frivolous ways.”

“In the north, they didn’t know him like they did down here—everybody knew him in the little bitty town of Atlanta, and obviously knew whose son he was. It’s not like he was trying to hide, but he just wasn’t finna disrespect his daddy or his daddy’s business.”

When Norris complained about being lonely at Harvard, his father wrote to him: “Go to church and serve the Lord, and then you won’t get lonesome.” Alonzo also chastised his son for lacking physical prowess, insisting that to enhance his mind Norris must strengthen his body.

“This was perhaps the most severe rebuke Norris had ever received,” Merritt wrote in “The Herndons.”

“Evidently, so stunned and ashamed by it, he fell silent. For weeks, he completely stopped communicating with his family.”

Norris would remain essentially muted for the rest of his life.

“In the north, they didn’t know him like they did down here—everybody knew him in the little bitty town of Atlanta, and obviously knew whose son he was,” Flores says. “It’s not like he was trying to hide, but he just wasn’t finna disrespect his daddy or his daddy’s business.”

A Quiet Force for Black Equality

Norris returned to Atlanta upon earning his graduate degree from the Harvard Business School, almost foreshadowing his aversion to social gatherings by not attending the commencement ceremony. After compiling record books for the insurance company as a child, shadowing agents as an apprentice when he was a teenager, working in the Atlanta office during summer breaks from college, and serving as a vice president after graduation, Norris assumed the presidency of Atlanta Life shortly after Alonzo died in 1927. The family firm’s assets grew astronomically during Norris’s 45-year stewardship, and his personal wealth was estimated at $100 million during what the company deemed its “gilded age.”

When researchers attempted to chart Atlanta’s power structure in the mid-20th-century, their efforts were complicated by the existence of a vibrant Black hierarchy that existed independently of the white establishment, as detailed by Gary Pomerantz in his book, “Where Peachtree Meets Sweet Auburn: A Saga of Race and Family.”

“While Coca-Cola president Bob Woodruff sat at the apex of power on the white side, aloof and almighty, the Black community had at its apex, the socially reclusive Norris B. Herndon,” Pomerantz wrote. “Like Woodruff, Herndon operated through other men and did not actively participate in local civic groups. Through these civic operatives, Woodruff and Herndon pushed the necessary buttons to get deals done.”

Surprisingly, the existence of a Black elite wound up being a unique challenge for students of Atlanta’s historically Black colleges and universities as they joined youth across the country who were rising up for civil rights. While many privileged Blacks were wary of disturbing a status quo in which they had a degree of power, Norris and his associates were among the exceptions to wholeheartedly support the nascent revolution, recalled Lonnie King, founder of the Atlanta Student Movement.

“Atlanta Life Insurance Company was one of the strongest supporters of the Civil Rights Movement during the time I was in it, and I learned later that they had a history of doing that,” King said when interviewed by Merritt for the “Voices Across the Color Line” oral history project. King was summoned to the Atlanta Life offices after his group’s first demonstration and told the students’ picket signs looked raggedy, so Atlanta Life would direct its print shop to produce more appealing signage for all future protests.

Jesse Hill Jr. augmented his work as a junior officer at Atlanta Life with tireless civil rights activities. Young and provocative, Hill occasionally consternated his older colleagues with efforts such as quantitatively disproving the notion that Atlanta was a city “too busy to hate.”

“So many people, and mostly Black, would say, ‘Mr. Herndon, this young fellow you got here…’” Hill recounted to Merritt for “Voices Across the Color Line.” “Herndon wouldn’t hear any of it, and he would get the word to Mr. [Eugene] Martin, [executive vice president of Atlanta Life], and because of Mr. Martin and Mr. Herndon I was able to do a number of things.”

“Norris was a very modest man. He wasn’t a boastful kind of person. He gave generously without any publicity. He gave generously to anything that helped uplift Black people in this town, especially the colleges.”

The breadth of Norris’s generosity will likely never be known, “since he apparently was prone to impulsive gifts made more or less out-of-pocket,” according to an account of his life in the Atlanta Journal newspaper. Still, the historical record overflows with confirmations of his charity and commitment to Black liberation:

When a teacher at the Ashby Street School was preparing to file a lawsuit for equal pay for Black teachers in the 1940s, Atlanta Life recognized the potential risks and offered him a job if he was fired by the school board, which he was;

When Norris saw the women of First Congregational Church of Atlanta ferociously fanning themselves during a service, he paid to have air conditioning installed;

He was a faithful patron of the historic Butler Street YMCA and the institutions that comprise the Atlanta University Center, paying for new gymnasium floors, marching band uniforms, Atlanta Life advertisements in student newspapers, and donating almost half a million dollars to Morris Brown for the construction of Herndon Stadium;

He regularly sent checks to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, NAACP, and other groups leading the Civil Rights Movement and helped endow a bail fund for when protestors were arrested;

In addition to holding the life insurance policy for Martin Luther King Jr. (who was too high risk for mainstream insurers), Atlanta Life turned its building on Auburn Avenue into the financial headquarters and a satellite training ground for the Civil Rights Movement. Several activist groups convened in its conference rooms weekly, while Herndon directed his employees to use their lunch breaks to staff the picket lines during student demonstrations.

“Norris was a very modest man,” Atlanta Life executive E.L. Simon said in eulogizing Norris after his death in 1977. “He wasn’t a boastful kind of person. He gave generously without any publicity. He gave generously to anything that helped uplift Black people in this town, especially the colleges.”

‘A Sissy’ in Seclusion

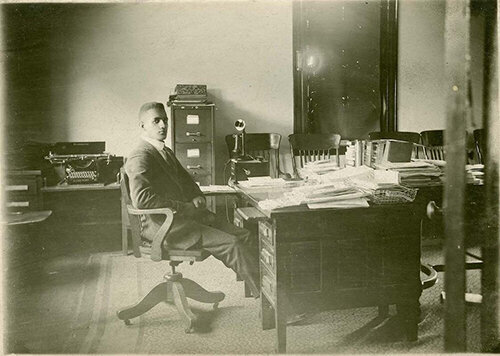

Norris’s low-key nature extended to every aspect of his life, a steadfast secrecy that partly explains why critically few people know his story today. He declined invitations to insurance industry conferences and speaking engagements, appeared at the Atlanta Life offices so infrequently most employees had no clue what he looked like and was teased on the cover of the October 1955 issue of Ebony Magazine as, “The Millionaire Nobody Knows.”

“His passion for anonymity has been carried to such lengths that few people know he exists,” Ebony wrote in the accompanying article. Indeed, there are few references to Norris in media that do not include phrases such as, “quietly, carefully buffered from public view” and “reticent and introverted,” or note how he “shunned publicity.”

“He clung tenaciously to a very private existence and, even as the head of a growing firm, avoided taking a public role in the firm or the profession,” historian Alexa Henderson wrote in her 2003 book, “Atlanta Life Insurance Company: Guardian of Black Economic Dignity.” “He appeared to become more reclusive and spent his time traveling, enjoying the arts, and hosting small whist parties attended by a small coterie of longtime friends.”

There are virtually no known accounts of Norris’s private life, but a 1977 letter from a Mrs. M.G. Howell to her father offers the tiniest glimpse into how he interacted among acquaintances at the Herndon Home.

“Jennifer and I had a delightful visit with Mr. Herndon this afternoon. While there, we met Mr. Johnson Hubert, who invited us to visit the First Congregational Church, where he is the music director. He also mentioned that he was with the music department at Morris Brown—which Mr. Herndon promptly corrected by telling us that he is the head of the music department at the college.

Mr. Herndon certainly is knowledgeable about Atlanta history—Mr. Hubert’s pride in the age of the Congregational Church (est. 1867), as the oldest Black church in Atlanta, was put down a small bit when Mr. Herndon reminded him that Bethel was older. A bit of history may be passing. Mr. Herndon does not like the ‘new’ term ‘Black’ – preferring ‘colored.’ As he said, he is not Black; Mr. Hubert is not Black – they are colored. Mr. Hubert deferred he uses the new term because the students prefer it. Jennifer loves the house – enjoyed going down the stairs and elevator. She showed Mr. Herndon how to use her calculator, and he was suitably impressed.”

However discreet Norris was about his sexual orientation, it was “common knowledge among Norris’s circle of friends and business associates that he was homosexual,” Merritt wrote in “The Herndons.”

He apparently had a disposition sweet enough to also be clocked by peers within his social class.

Irene Dobbs Jackson used to visit the Herndon Home to play the family’s piano, but as an ambitious bachelorette in a family of social climbers, she was warned by her father, John Wesley Dobbs, to keep clear of Norris.

“Norris had a reputation of being a sissy,” Jackson, who would become the mother of Atlanta’s first Black mayor, Maynard Jackson Jr., said in “Where Peachtree Meets Sweet Auburn.”

“Daddy would say, ‘Leave him alone and don’t invite him over here.’”

“However discreet Norris was about his sexual orientation, it was ‘common knowledge among Norris’s circle of friends and business associates that he was homosexual.’”

It can be hard to recognize any heroism in how Norris shrank away from society and walled himself inside the Herndon Home, but Jackson’s memory vindicates some of his choices.

Born in 1897, he was in his sixties before the word “gay” meant anything other than happy, and even older when the notion of homosexual rights materialized on the most outer fringes of Society.

He had only two options when it comes to his sexual expression, and being openly gay was not one of them. Like most men of his era with same-sex attractions, he could’ve suppressed those feelings enough to engage in the pretentious courtship of the times, while indulging his desires through clandestine encounters; or he could’ve savored the solitude in a world of his creation.

Under incredible pressure to marry due to his legacy, class, and the conventions of 20th century America, his resistance becomes legendary. He left no girlfriend, widow, or other ambiguity about his sexual interests while forcing his contemporaries who were writing about him to come up with their most creative, respectful way to call him a queer.

Herndon Legacy Incomplete and Facing Extinction

To the extent anyone is telling Norris’s story today, there is no unified messaging about his biography. Atlanta Life board president Giles, who also chairs the board of the non-profit Alonzo F. and Norris B. Herndon Foundation noted that Norris was gay in the online presentation he made for Business Insurance’s Diversity and Inclusion Institute; but other

Herndon Foundation leaders are less certain of that conclusion.

“We can never tell for sure, we can only speculate,” says Elsie McCabe Thompson, who serves on the boards of Atlanta Life and the Herndon Foundation. “We’re only guessing. We don’t have anything written that proves he was in the LGBTQ community – all that was said was that he never married and was childless.”

However, much about the Herndons remains unknown because the family’s archives are in the basement of the Herndon Home and off-limits to researchers and journalists. When students of the honors college at Georgia State University sought to create a money trail from the Herndons to civil rights causes, their efforts were abridged by the Herndon Home archive policy.

“I still think it would be a great project to try to trace their contributions and try to quantify their contributions to the Civil Rights Movement, but without access, it’s hard to do,” says Sarah Cook, interim dean of the GSU honors college.

Thompson, who was the only Herndon Foundation trustee to respond to interview requests, cited cost and security concerns to explain the archive restrictions. There is no longer any paid staff at the Herndon Home, which is a designated historic landmark and museum that used to offer daily tours. According to its website, which lists an out-of-service telephone number, the home’s operating hours have been reduced to Tuesdays and Thursdays, but no one was present during recent attempts to visit the museum.

“Someone would have to be there to watch because we wouldn’t want anything to be compromised, or lost or stolen because it is part of a legacy, a cherished one as far as I’m concerned,” Thompson says. “A document, for instance, is easy to slip out, easy to be stolen. I’m not suggesting anyone would do it with malintent, but we want to make sure everything is preserved for future generations.”

The budget woes that have plagued the Herndon Foundation for decades can be confounding since Norris created the entity explicitly for the perpetuation of Atlanta Life and the preservation of the Herndon Home. Norris owned between 70-90 percent of Atlanta Life’s stock when he died in his sleep in June 1977, and bequeathed the entirety of his fortune to the Herndon Foundation, which maintains a controlling interest in Atlanta Life today.

However, there is a chasm between the non-profit’s assets and cash flow, recalls Nancy Boxill, who used to represent Vine City on the Fulton County Commission and formerly served on the Herndon Foundation board.

“The Atlanta Life stock is not publicly traded, so if one share of the stock is worth $10 or one share of the stock is worth $1 million, it’s not publicly traded so you can’t go out into the market and sell it,” says Boxill, who moved from Atlanta and ended her term as a Herndon trustee years ago, and does not know if the same budget structures remain. “So while you may have stock, it doesn’t have a readily attainable liquid value.”

Still, when Giles talks about the Herndon Foundation, it does not sound like he is describing an organization that cannot afford to hire its own essential staff.

“We can never tell for sure, we can only speculate. We’re only guessing. We don’t have anything written that proves he was in the LGBTQ community – all that was said was that he never married and was childless.”

“The Alonzo and Norris Herndon Foundation owns 73 percent of Atlanta Life Insurance Company – the Atlanta Life Insurance Company is owned by the community, not by normal shareholders,” Giles said in the Diversity and Inclusion online seminar.

“So the community is Atlanta Life. So when customers partner with Atlanta Life they are directly partnering with the community, and the community investments that the Herndon Foundation makes: in first responders, in helping inner-city kids learn entrepreneurship, helping the historically Black colleges with scholarships, and helping with operational expenses, in supporting the King Center, the Robin Hood Foundation, the Innocence Project, the NAACP, the Urban League and giving scholarships. We exist for the community, that’s what we exist for.”

That mission is evident at neither the abandoned Herndon Home nor the impoverished neighborhood that has surrounded it for decades. Most of the Herndon Foundation’s operating budget, Thompson says, is devoted to The Herndon Directors Institute, a training academy for underprivileged, high-achieving professionals who aspire to sit on corporate boards.

“It’s not an inexpensive program [for the Foundation to operate] because we specifically do not charge [tuition],” says Thompson, who notes the training was developed and administered by the Herndon Foundation.

“So many board-readiness initiatives charge money, and we are painfully aware of the fact that most minorities are overqualified because they’ve gone to some of the best schools, etc., and they have been underpaid, historically, for their work, and they may be the one person in their family who has been successful financially. We don’t want to charge them because they may be supporting a larger group of family members, they may have student debt associated with loans for prestigious institutions, so we don’t charge anything,” Thompson adds.

“One of the things we advise all of our fellows is that it’s an extremely expensive program, and we want our fellows to pay for it not to the Herndon Foundation, not to Atlanta Life, but by paying it forward to everyone else for a lifetime.”

When asked for a list of participants in the Herndon Directors Initiative, Thompson referred to the Foundation’s website, which did not contain a roster of alumni or corporate partners, testimonials from graduates, or insight into the curriculum.

While the Herndon Foundation is formally charged with keeping the Herndon legacy alive, other institutions have felt an obligation to ensure the stories of Alonzo and Norris are not erased from Atlanta’s memory. In 2019, the Sweet Auburn Works non-profit placed posters of Alonzo, Norris, and other Atlanta Life luminaries on the boarded-up windows of the former Atlanta Life building on Auburn Avenue. Next door, GSU has erected historic signage to share an outline of the Herndon story, and its honors college has offered a Herndon-focused research class for about five semesters.

“When I learned that we were going to be moving [onto this site], I thought how perfect,” Cook says of the honors college, which she wanted to name after the Herndons but was unable to do so due to the financial politics of university development. “We decided that since there wasn’t going to be a linear pathway toward naming the college, we would teach students about the Herndon family and their legacy.”

In 2017, the honors college’s Herndon Human Rights Initiative received a $200,000 grant from the Rich Foundation, which includes a scholarship for a student whose studies focus on civil rights. Although a plurality of GSU students are African-American, it is not an HBCU and was given an academic side-eye by some who wondered if it was the proper institution to tell the Herndon story.

Representatives from Morehouse College, Spelman College, Clark Atlanta University, and Morris Brown College did not respond to inquiries about whether any buildings or scholarships are named after the Herndons, any courses taught on their history, or if new-student orientation includes any reference to the family that placed no cap on its financial support of the schools.

The Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library is a potential repository for the Herndon archives, given its existing staff that knows how to assist with archival research; or, the papers could be transferred to the Auburn Avenue Research Library, which already houses the Atlanta Life Insurance Company files that were the source of much of the content in this article. Either way, the Herndon legacy cannot survive if it is not known.

“What was once current, naturally over time becomes part of history, and unless one is committed to continuing to tell and retell historical facts, I think that’s just what happens—memory fades,” says Boxill, who hopes the Herndon archives are opened to researchers.

“History serves us best when it is as full and complete as it can possibly be. The richness of any person’s life, and the fullness of any person’s legacy, in my view, has its highest value when we have the complete story. The more we know, the fuller the recounting, the better off we are.”

Sadly, most modern Atlantans with any familiarity of the family name think of the old Herndon Homes, a housing project torn down in 2010. This represents a citywide failure—by the local governments, HBCUs, LGBTQ organizations that leverage references to the Civil Rights Movement in the name of intersectionality, and even Atlanta’s hip-hop moguls who ought to idolize the Herndons, even if they do not share Alonzo and Norris’s predilection to give away their wealth.

“C’mon, this can’t be the actual Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, where his house is, where his actual footsteps were—his footprint is in that neighborhood,” Flores says of the indefinite future of Vine City and the Herndon Home. “Dr. King was able to do what Dr. King did because of the funding he was able to get, and that came from the Herndons.”

To learn more about Norris Herndon:

Gay and Lesbian Atlanta By Wesley Chenault and Stacy Braukman

The Herndons: An Atlanta Family By Carole Merritt

Atlanta Life Insurance: Guardian of Black Economic Dignity By Alexa Henderson

Make A Donation To CNP

CNP was founded to answer the call put forth by Bayard Rustin, Essex Hemphill, Marlon Riggs, and James Baldwin. Your generous donations help to support this special event and to further the mission of CNP.

Ryan Lee is a freelance writer in Atlanta and a columnist for The Georgia Voice, which focuses on LGBTQ issues in the south.