The Curious Case of Tevin Campbell

Tevin Campbell has been in the news again, this time for all the right reasons. With new opportunities coming his way this summer on OWN’s “Queen Sugar,” I decided on the anniversary year of his auspicious launch, we should review what made him great to begin with and how he fell so suddenly and tragically from grace.

Thirty-years ago this year, the world was introduced to the elastic, richly textured instrument of one Mr. Tevin Campbell. Shepherded into the offices of Warner Bros. Records by jazz pioneer Bobbi Humphrey and signed by Warner Bros. renowned Senior Vice President of Black Music, Benny Medina, the then-12-year-old singer would be launched into the public consciousness by no less than the iconic Quincy Jones. If that start wasn’t impressive enough, Campbell’s 1989 debut single with Jones would eventually become a #1 hit on the Billboard R&B charts, “Tomorrow (A Better You, Better Me),” somewhere around the same time Campbell was just turning 14. Partially driven by a single that would, for a time, be a hallmark in the graduation auditoriums of schools, teen talent shows, and youth choirs in churches across America, Back on the Block would go on to win the Grammy for Album of the Year.

Did I mention that Campbell’s follow-up collaboration would be with none other than Prince, when he was just 15, for the Top 15 Billboard Hot 100 “Round and Round” (peaked at #3 R&B)? By 18, there were only three voices allowed to vamp out in both adlib and in keys higher than everyone else on 1994’s Black Men United’s sole charity single, “U Will Know,” written by D’Angelo, and they were Stokely Williams, Brian McKnight, and an 18-year old Tevin Campbell on a song that included everyone from Usher and Gerald LeVert to El DeBarge and Lenny Kravitz. This was the level of company Tevin Campbell was not only keeping but holding his own with, smiling confidently and shimmering with ingénue talent.

With a four and a half octave range, young Campbell was often referred to as the male Whitney Houston of his day by those who closely studied vocal technique. Campbell had so clearly researched Houston’s approach to song, right down to her riffs, runs, and builds, that his altino countertenor on Alan and Marilyn Bergman’s 1992 Quincy Jones’ produced “One Song” off of the official Olympics Barcelona Gold album so completely followed the 1988 blueprint for “One Moment In Time” that one could be forgiven for believing the song was Houston’s (she would go on to perform it live repeatedly for presidents and in concert thereafter). Campbell would be called to slay ala Houston style again at age 20 on the 1996 Olympic album for “The Impossible Dream.” Of the five Grammy nominations he’d receive before his 20th birthday, Campbell lost to the likes of Luther Vandross, Al Jarreau, Ray Charles, Babyface, and peak Boyz II Men, that’s the level of artistic competition he was considered in the company of in 1991, 1993, and 1995, respectively. In addition to selling over three million albums during this run, did I mention Campbell acted in sitcoms and cop shows alongside such talents as Will Smith and Brandy? That a generation of grown-ups known him best for his cult classic role as Powerline and for killing the songs for Disney’s A Goofy Movie in 1995?

It is this kind of storied beginning that made Tevin Campbell fans go completely in on author and social influencer blogger, Luvvie Ajayi aka Awesomely Luvvie, when she dared on August 16, 2018 to say the following:

“Someone suggested Tevin Campbell to sing at Aretha’s tribute. Under what rock did they pull that name from?”

And, it wasn’t just every day fans that dragged Luvvie so hard following the quip that Tevin Campbell trended on Twitter for days thereafter, celebrities chimed in too. Wale, Missy Elliott, Roxane Gay, Tika Sumpter, Michael Muhney, and director Ava DuVernay, among others, all came roaring to the defense of Campbell, the latter publicly stating that she’d be booking Campbell on forthcoming episode of Queen Sugar just to learn these disrespectful millennials. Reportedly, DuVernay has made good on that promise and Campbell premieres this summer.

Following takedowns in nearly every Black media outlet, within 24 hours, Luvvie bowed down and tried to play like she ain’t mean it like folks took it, dayum. She “know he can blow.” Uhmmm hmmm…

For his part, Campbell, with the utmost of class, thanked his fans and in the slyest bit of clapback posted a picture of him young, bright, and beautiful beaming with Aretha Franklin while subtly mentioning all the times he was in the Queen of Soul’s company, making the prospect of him publicly honoring her not so far-fetched in either talent or relationship. It was the kind of wink and a nod that had always been signature Campbell. That same knowing twinkle that can be seen in his eye during the “Can We Talk” video, one of mischief and assurance. And, it made me wish those same fans and celebrities had rallied around him back when it might have mattered most, from 1997 to 1999, when Campbell experienced a startling reverse alchemy of a golden career that turned to lead right before our and his very eyes.

Reflections on Music, Identity, and Belonging

With just a little over a year separating us, Tevin Campbell’s rise and fall is forever intertwined with my own development as a young, Black, and gay person who grew up as an age peer to Campbell, so often did Campbell's music intersect and punctuate key periods of my own life. I remember watching the debut of the “Tomorrow (A Better You, Better Me)” video with my fellow teenage cousins and throatily singing along with lyrics we had memorized long before now legendary video came out. Even then Campbell was slyly enigmatic, bedazzled with a confidence that suggested he was the cocky kid who’d always been called upon to sing lead in every choir, talent show, and school play he’d ever been in since he first uttered words, taking it almost as a birthright. The kind of kid every other talented kid hated and wanted to be.

Watching that first video again as a 44 year-old man, one cannot help but be all the more astonished by the lad’s surety in a room conducted by the great, yet here unassuming Q with three generations of some of the greatest jazz and soul musicians who ever lived all teaching and playing in support of this wunderkind and an eager choir of young hopeful voices, all so bright, pure, and clean. If Campbell’s acting in the video, you can’t see the strings. He looks like he belongs in that room, as every bit the star. There’s also something too grown about him as well, something too knowing for his age. Handsome and cocky, but soft and aware too.

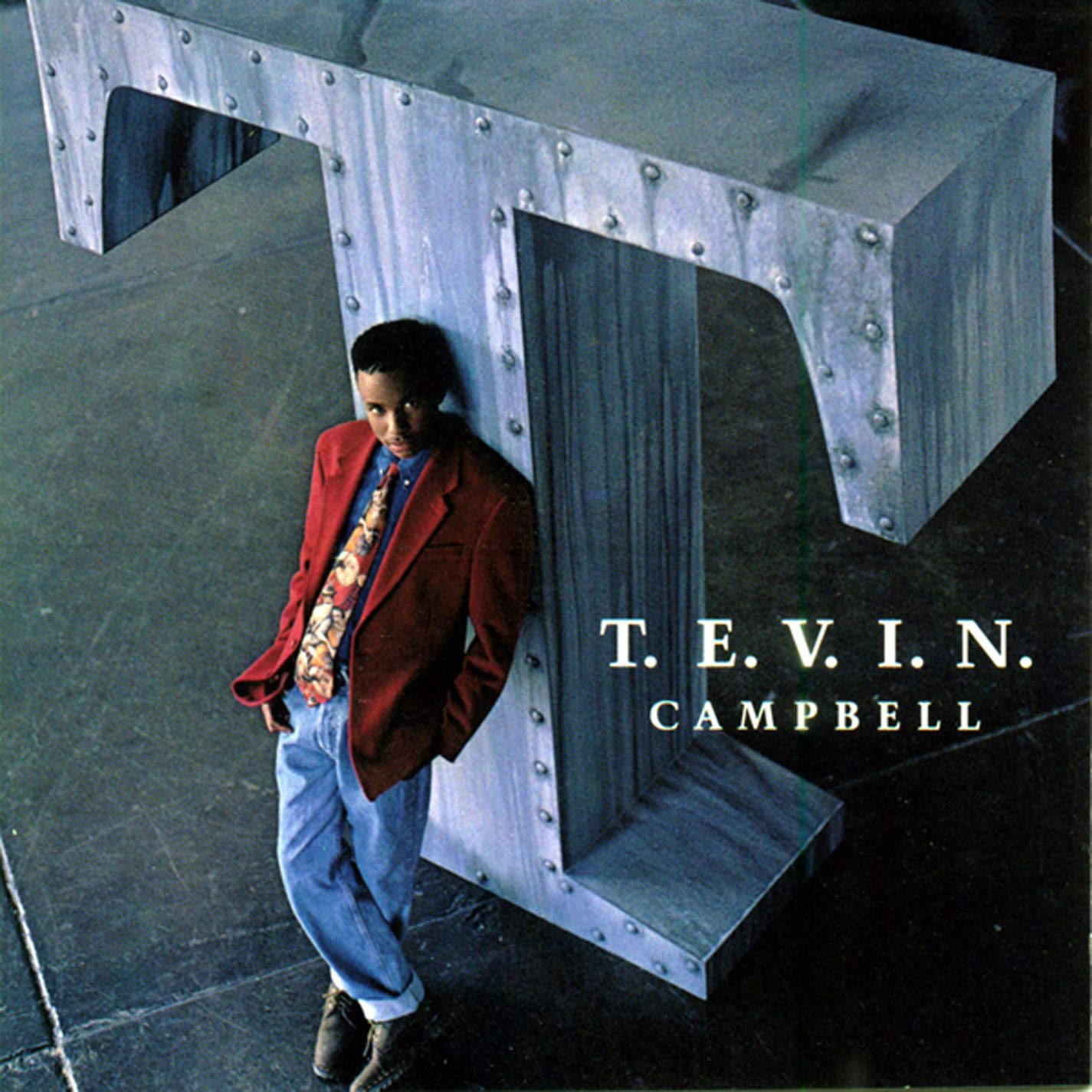

As someone who was performing and getting leads in school shows at the time, it was Campbell whose energy I tried to channel, but could never quite pull off with his Devil may care ease when I sung. Ironically, putting on the energy of Campbell drag was easier to pull off when T.E.V.I.N. came out and I’d be called upon to lip sync its #1 R&B hit, “Tell Me What You Want Me To Do,” as a rare male performer during drag shows in Chicago’s CK & Augies as a newly “out” 16-year-old, one also too knowing and aware for my age. Thin and lithe with identical haircuts, for a time, we favored. Both beloved and cherished by a certain crowd, yet not fully supported among the whispering rooms of barbershops, gyms, and other hyper-male spaces.

The period of 1993 to 1995 for Campbell is so lit, it might be hard to fathom today. He was the opening act for Janet Jackson’s Janet tour, which would be akin to opening for Beyoncé’s Lemonade tour for this generation. He had three top five R&B hits in a row from his multi-platinum, I’m Ready, album, including another #1 in “Can We Talk” (he’d have had two #1 with “I’m Ready” were it not for R.Kelly’s 12-week run with “Bump ‘N’ Grind” at #1) For his releases between age 14 to 16, Campbell was in studios recording with the likes of Prince, Babyface, Al B. Sure, Darryl Simmons, Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, and Narada Michael Walden – all R&B, pop, and soul royalty in the production game. The songs from that period would soundtrack my relationships, from the sweet introduction of “Can We Talk” to the relationship defense of “Always in My Heart” to the aching break-up of “Don’t Say Goodbye Girl,” back when you had to constantly substitute “boy” for “girl” in your head and on clumsily offered mixed tapes to boyfriends who couldn’t often help but be temporary given the immaturity of our age, the arrested nature of our development as boy children, and the prevailing homophobia of the era.

Homophobia would also prove to be the undoing of Tevin Campbell beginning with the styling for the first single for the video for his third album, 1996’s Back To The World, the first to be executive produced by Campbell and which featured production by Babyface, Stevie J, Jamey Jaz, Keith Crouch, Sean Puffy Combs, and Chucky Thompson. It only went gold after a run of pure platinum. I interviewed Rahsaan Patterson earlier this month and asked him about the infamous video and the drop-off in support by both Campbell’s label and radio when what began as a whisper about Campbell seemed confirmed by all things, a braided bob haircut, and some retro-70s disco styled clothing at the commercial height of rap music hyper-masculinity.

“It's interesting because you look at Back to the World and that album and you look at the simple fact that he had that hair at the time. The fact that the hair was the hair was really the only reason why that album didn't necessarily get the support that it deserved, a hairdo,” said Patterson.

More than a haircut, one identically worn by Larenz Tate as a murderous thug just three years before in Menace II Society, without so much as a peep, Campbell seemed publicly freer in a way that society wasn’t prepared to let a black lothario crooner be free anymore, the way they’d let artists like Sylvester and Jermaine Stewart be free just a decade before. Campbell wasn’t alone, the debut albums of Black men publicly perceived to be gay or bisexual were all considered commercial disappointments, despite charting radio cuts, largely because radio and their own labels failed to properly support them outside of a few key markets, including the 1996 -1998 debuts of Rachid, Billy Porter, Rahsaan Patterson, Jesse Powell, and the third album of Campbell. These albums still artistically hold up thanks to the sound song choices and the vocal might of these artists whose visual challenged the masculine iconography of their time.

Tevin Campbell’s Long Road to Rediscovery and Redemption

By the time Campbell was arrested in 1999 at the age of 22 for soliciting oral sex from an undercover cop and followed it with a disastrous “forced outing” interview with Jamie Foster Brown in Sister to Sister magazine in 2003, Campbell’s career as an A-lister had already come to a close. In the 20 years since, several times Campbell seemed to surface to an always eager fanship, such as his multiple runs in the international touring companies of Broadway’s Hairspray over six years, a briefly released Never Before Heard digital album in 2008 that was pulled and ethered, and a smattering of tribute shows, late night TV guest appearances, one-off singles and guest features on other’s projects kept him episodically busy. Much lauded performances in 2014 at the Essence Music Festival and New York’s B.B. King culminated in the opportunity to record and release a live concert DVD that showcased Campbell still able to capably hit every note, but tonally needing to drop the keys for his comfort and our own as his unique timbre has thickened and grown heavier with age. Despite these comeback moments and the fans’ responsiveness to them, nothing seemed to stick, as if the world that had grown up to allow gay marriage wouldn’t really allow Campbell to grow past that one youthful moment in 1999. Imagine being trapped by an incident committed before your 23rd birthday?

It was also at this point where my personal path as a BGM and advocate radically diverged with Campbell, him seemingly reclusive and cantankerous in media interviews, unable to transition with this new age of transparency and publicly queer radicalism, to own his space in the pop and soul lineage that would later make someone like Todrick Hall or B.Slade even possible.

Admitted experience with substance abuse and a brief, but reportedly transformative jail stint suggests the transition from golden boy to pariah took its toll on the child star turned awkward and confused grown-up. Among some members of the gay community, Campbell doesn’t help his cause or comeback, responding to interview questions in IMissTheOldSchool.com about his sexuality as recently as December 2009 with a curious mix of defensiveness, denials, obfuscation, and old school industry lines about it being “nobody’s business” and “I like to leave a bit to the imagination,” both of which are his right, even as they sound tone deaf to this age. In the handful of interviews Googleable since 2003, Campbell has maintained that he’s not gay and his experiences at the time are part of a period when he was “lost” and “acting out,” a period in 2003 when he was describing himself as a “try sexual” and “a freak,” and have no bearing on who he is or his sexuality today, a sexuality where he likes “a lot of different things.” Out of compassion, you can feel yourself trying to shove the word “pansexual” in his mouth to help correct the layers of potential offensiveness coating his lack of media savvy response.

As late as October 15, 2018, Campbell was responding to critics on Twitter with the following, words with echoes of the assured 14-year-old boy who knew his gifts would make room for him: “I read the comments I done heard it all “his a$$ loose, he a fag, he gay as hell,” y’all homophobes gotta do better the thing you will NEVER EVER be able to say about me it “that boy CANT saing” that’s the day I will be sitting at home crying and that day will be NEVER.”

With DuVernay providing yet one more time at bat, one more moment of trend worthy earned media that could be capitalized on with a fresh new project, a better public understanding of self, and a powerful media statement of candid personal truth, Campbell could return to his rightful place as an heir apparent in soul, reminiscent of a time when he and Usher inexplicably were peers. At 43, it’s possible for him to have in 2019, what 1999 refused to allow him to have some 20 years ago. The foundation was already laid by the hard work and natural talents of the 14-year-old with the Houston pipes and the Dallas charm. Maybe this time both Campbell and his fans will embrace the rest of him in the room on that stage too. It’s past time for us all.

Cover Photo: T.E.V.I.N. album cover

L. Michael Gipson is a writer, educator, and 24-year advocate for a host of social justice causes, L. Michael Gipson, MS is the co-founder of the Beyond Identities Community Center for LGBTQ youth in Cleveland, the Black Alphabet Film Festival in Chicago, and the Black Bear Brotherhood in Detroit. Currently, Gipson is the Founder and Principal of Faithwalk, LLC and the Urban [W]rites project. A Red Dirt Press author, Gipson serves as Editor-at-Large at SoulTracks.com and Lead Writer and Co-Producer of the PBS docuseries Indie Soul Journeys.