The Rebirth of Dr. David Malebranche: How A Devastating Loss and Professional Detour Fueled A Comeback

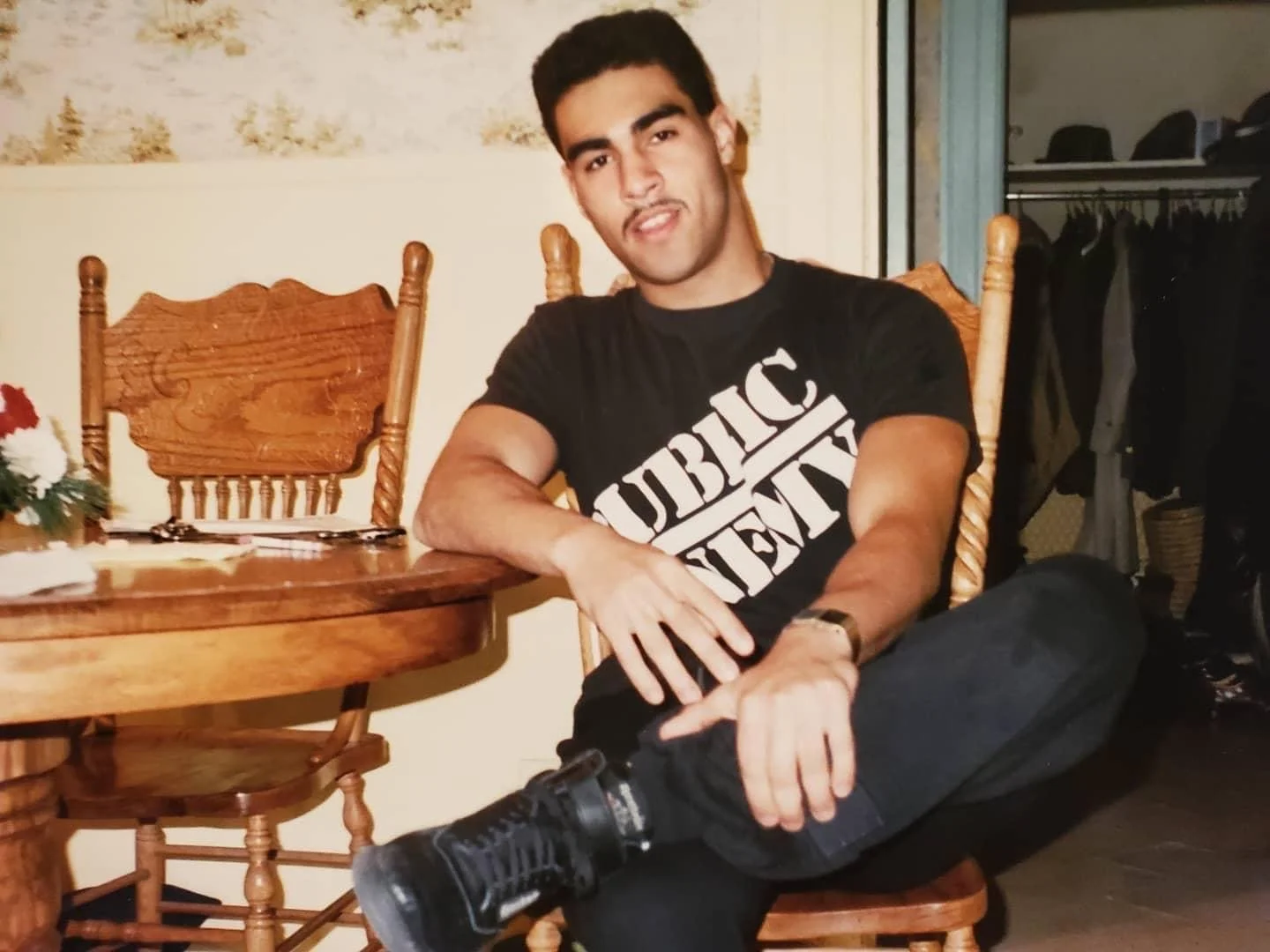

There was a bedtime and morning ritual in the Malebranche household. A kiss from the family patriarch to his son David and daughter Michelle that was so routine—his decision to replace David’s kiss with deafening silence—reverberated loudly throughout their home in Schenectady, NY, in the summer of 1993.

Despite being an exceptional student with degrees from Princeton, Emory, and Columbia Universities, Malebranche, now 53, had become accustomed to achieving a level of success that appeared to impress everyone but the Haitian-born surgeon he called dad. Yet he was not accustomed to being viewed as a disappointment by the man he idolized.

“Donna, is our son trying to tell us something?” Malebranche recalls his father asking his mother almost daily, particularly after getting his ears pierced, and choosing to wear an earring in the right ear only on this particular day, which in the early 90s was a cultural indicator that a man was not heterosexual.

“He would ask her that question every morning. He would not let it go,” Malebranche said. “So after the third or fourth morning, she'd say, ‘What do you want me to do? I can’t cover for you.’”

“I'm 23. If he's not man enough to ask me directly, he’s not man enough to hear it from me, so you tell him,” he said. “And so she did. Those three days that I was home, he didn’t speak to me at all.”

Malebranche tells The Reckoning that his mother kept his secret from his father for over a year. She was first confronted with the possibility that her son might be attracted to men upon opening and discarding mail from the now-defunct Black porn company Black Forest Productions.

“We can’t tell your father,” she said at the time. “It’ll kill him.”

But his secret was now out in the open, with the elder Malebranche making his disappointment with his son’s truth abundantly clear.

“Basically, the gist of it was, all my dreams are dashed because you're gay,” Malebranche said, through the kind of laughter that is only possible with time and healing.

“We cried a lot. We got a lot of stuff out,” he said. “I drove from upstate New York all the way back to [Michigan State University] East Lansing, Michigan, that night. I got in at maybe nine o'clock in the morning and just passed out and slept—probably one of the best sleeps of my life because it was finally done.”

Same Gender Loving

It was during undergrad at Princeton University that Malebranche began actively exploring his sexuality—falling in love with a friend whom he frequently DJ’d parties with, and making up for the lost time in what he describes as a repressed childhood that focused more on academic performance with very little room to explore dating and relationships.

“The very first time I experienced an orgasm was watching Billy Ocean on Saturday Night Live,” Malebranche said.

Though the “Caribbean Queen” singer was fully clothed, he vividly recalls being drawn to the singer whom he describes as being “attractive as hell.”

Malebranche, who identifies as same gender loving (SGL), a term created by activist Cleo Manago meant to encompass both the cultural identity and same-sex attraction of Black people while detaching itself from the identifiers commonly associated with white gay culture. Manago, according to Malebranche, asked the right questions that set him on a path towards self-discovery.

“He challenged why I called myself gay, which he does with everybody. And I had to explain it. And the funny thing was, I couldn't really explain it.”

“I’m a firm believer that anyone can claim whatever label they want to. So whether you call yourself gay, queer, or SGL, whatever you want to call yourself, if it works for you, if it makes you a better person, if it helps you make sense of the world it’s fine.”

Malebranche tells The Reckoning that it was the inclusion of the word “loving” in SGL that moved him to embrace the term.

“I’m a firm believer that anyone can claim whatever label they want to. So whether you call yourself gay, queer, or SGL, whatever you want to call yourself, if it works for you, if it makes you a better person, if it helps you make sense of the world it’s fine,” he said. “But I'm not about people trying to change the way I self identify.”

If there is one thing that Malebranche is clear about beyond self-identification, it is personal autonomy when it comes to the sexual experiences of Black SGL men.

“I’ve never been the condom police,” he said. “My attitude was never [you must] use a condom. My attitude is; get your freak on and figure out what you need to do to protect yourself best. Get tested. Live your life. Have your experience. Have your pleasure.”

Malebranche admits that his history with condom usage has been “scattered.” And in 2007, with a decade under his belt as an internal medicine doctor specializing in HIV, he was about to find himself on the other end of patient care.

Courage In Crisis

“I remember being so tired that I laid down on the carpeted floor of my office and just curled up in a ball,” Malebranche said, as he recalled the extreme fatigue he experienced upon returning home to Atlanta following a business trip to Philadelphia in November 2007. “I finally got to a point where I was like, okay, what's going on?”

Malebranche says he immediately made an appointment with his then primary care physician, Dr. Jeffrey Rollins of Midtown Medical Associates, who initially believed he was experiencing an inflamed prostate. Malebranche remembered that his last HIV test was over two months ago, and although the result was negative, he asked to be tested again.

“November 28th, 2007, I was sitting in Midtown Landmark Theatre watching “No Country For Old Men,” he said. “I saw a call from Dr. Rollins' office come up on my phone and I just forwarded it to voicemail and then finished watching the movie. I came out and listened to the message: ‘Hey, David, it's Dr. Rollins. If you could give me a call, I just want to go over your lab results.’”

In the nearly five years of their doctor/patient relationship, Rollins had never called Malebranche to discuss lab results. He tells The Reckoning that he was prepared for whatever news Rollins had to share.

“I remember a wise counselor from Michigan State told me, she said, ‘whenever you come in, I want you to think about what you would do if that test came back positive.’ So I was always in that mindset,” Malebranche said.

“One thing is that your HIV test didn't turn out so good,” he recalls Rollins saying over the phone.

“When I found out, I just kind of sat there,” Malebranche said. “I took a few selfies on my phone because I wanted to capture that moment. I wanted to be like, remember when you took these pictures? This was when it happened.”

Because of the acute infection, Malebranche says his viral load was 1.5 million. And like most HIV specialists in 2007, Rollins was faced with the dilemma of whether to advise Malebranche to begin treatment immediately or to wait. He deferred to Malebranche’s expertise.

“I remember a wise counselor from Michigan State told me, she said, ‘whenever you come in, I want you to think about what you would do if that test came back positive.’ So I was always in that mindset.”

“I said, Dr. Rollins, I need you to pretend like I'm any other patient that comes in with the same scenario. What would you tell them to do?”

“I would tell you to start taking the medication,” Rollins said.

“Good,” Malebranche replied, before receiving a prescription for what was a commonly prescribed antiretroviral regimen at the time.

If there was any discussion about the impact of Malebranche’s diagnosis on his career and public image, it was not a conversation he was having internally, nor was he allowing himself to be engulfed in shame following his diagnosis.

“I'm human. I would not be embarrassed to get high blood pressure because I'm eating too much salt or because I’ve gained weight because I'm eating too many fatty foods. Healthcare providers are flawed human beings, just like every other person on the planet,” he said.

“My attitude is; get your freak on and figure out what you need to do to protect yourself best. Get tested. Live your life. Have your experience. Have your pleasure.”

- Dr. David Malebranche

For Malebranche, his diagnosis was a wake-up call and an opportunity to reevaluate certain areas of his life that no longer served him.

“It took me about five years, but I would say the diagnosis is what gave me the strength to leave [the Associate Professor of Medicine role at] Emory when I did,” he said. “I experienced my share of microaggressions with some staff at Emory in the mid to late 2000s. While I loved a lot of my co-faculty and a lot of people there, as an institution, I felt very devalued and disrespected. And I think the diagnosis gave me the courage [to be] done.”

Following his exit from Emory, Malebranche spent the next three years at The University of Pennsylvania before returning to Atlanta in 2016 to accept a job as an infirmary physician with the Cobb County Adult Detention Center. Malebranche left that role after a year over philosophical differences in the level of care given to inmates before landing at Morehouse School of Medicine as an Associate Professor of Medicine—a position he’d relinquish to take care of his father in the final days of his life.

Lose To Win

In the blink of an eye, the elder Malebranche went from being the go-to source for medical care to a reluctant patient diagnosed with critical limb ischemia—a severe blockage in the arteries of the lower extremities, which markedly reduces blood flow.

“We found out that two of his three blood vessels were completely blocked. And the only option he had at 87, was a bypass similar to the way they bypass in the heart,” he said.

Malebranche tells The Reckoning that he took a leave of absence from Morehouse. He temporarily relocated to upstate New York to assist his mom with caring for his dad, using all of his sick and vacation time in the process.

It was becoming increasingly clear to Malebranche and those close to him that his father’s time was running out.

“The death of a parent kind of reorients you. I just didn't feel like going back and fighting people with the same level of energy I had before he died.”

- Dr. David Malebranche

“One of my friends asked me, she said, ‘What is your dad holding on for?’”

“I think he was worried that if he left this earth, the rest of the family would fall apart,” Malebranche said. “I had to sit down with him and my mom. I said we were going to be okay. He didn't say anything to me. He just kind of looked out of the window,” Malebranche recalls.

When his father did speak, he had one request: to make it through one more holiday season.

“He wanted to see his grandkids. He wanted to see my sister. And he did. They came home. So we had one last holiday season with him. I think he knew he wasn't gonna make it,” Malebranche said.

Dr. Roger J. Malebranche passed away peacefully on January 17, 2020.

The man who was revered by his son, who inspired him to write the 2015 memoir “Standing on His Shoulders: What I Learned about Race, Life, and High Expectations from My Haitian Superman Father,” was gone—and Malebranche would never be the same—isolating himself from the world amid the insurgence of COVID-19 for the next two years and separating himself from Morehouse permanently.

“The death of a parent kind of reorients you. I just didn't feel like going back and fighting people with the same level of energy I had before he died. I cleared out my retirement from Morehouse School of Medicine and just started hustling,” he said.

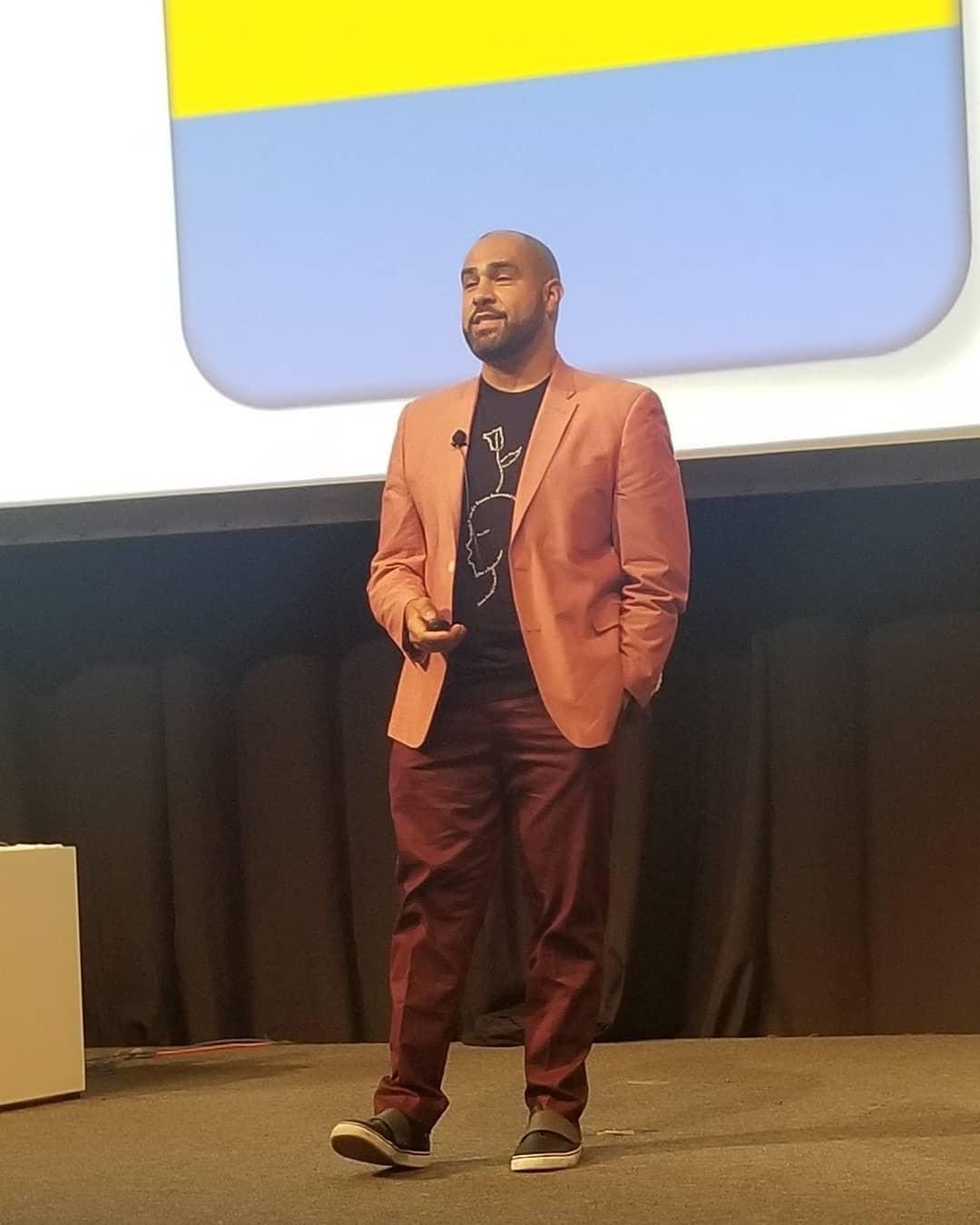

Malebranche worked freelance medical education jobs until several full-time opportunities presented themselves, one of which he says sent him reeling after an offer with a start date fell through. Malebranche says he proceeded with caution, only telling a select few about the process he was undergoing for the role of Senior Director, Global HIV Medical Affairs at Gilead Sciences, a job he was ultimately offered.

“Gilead presented the biggest challenge for me,” he said. “I can strategize about getting medications to the places and people that need it. It's about training healthcare providers to do the right thing with the medications. And I love doing that stuff. So, it gives me an opportunity to work not only on a national level but on a global level.”

Malebranche says his new role at Gilead represents a fresh start.

“What the new start with the Gilead position represented to me was an acknowledgment that my father did pass. He's gone and I have to move on,” Malebranche said. “I’m just tremendously thankful for the opportunity. Not because I didn't think I was worth it. But because it came at the right time and saved me.”