Reflections of a Body Outsider (Part 2)

L. Michael Gipson

Living somewhere in between the harsh, reality-based vulnerabilities of Roxanne Gay’s memoir of her love/hate relationship with her “unruly body” in Hunger and the unrelenting step-into-your power body positivity of Sonya Renee Taylor’s radical self-love bible and movement, The Body Is Not An Apology, I am some days faking it until I’m making it and some days radically embracing of my bear size. At 6’2 and 360 lbs of structured fat and muscle, there are no cute euphemisms like “thick” or “husky” to describe what is undeniably a large frame. And, little is said of men like me in our culture and literature, made invisible by even a body positivity movement that is largely dominated by cisgender straight women. And, less still among those of us who are Black gay men of size in a world that loves nothing in those descriptors.

Just as it took a process of time, reading, living, and loving to come to a state of radically loving my Blackness and my gay identity, so is it to accept this body and all that comes with it. It has been a process assisted by the words of folks like Gay and Renee, Black feminists who know something about what it means for the world to tell you that you’re undesirable. I desperately needed their help, having not always been a size 46 in the waist. It has taken more than a decade to relax into this identity of “bear” and have it become a comfy fit (and, yes, I’ve heard the concerned Black gay nationalist arguments of adopting yet more white gay cultural language by using terms like “bear,” but I can’t really embrace the term “boy” at a smooth and grown 43-years-old in any context, even one intended to be culturally affirming).

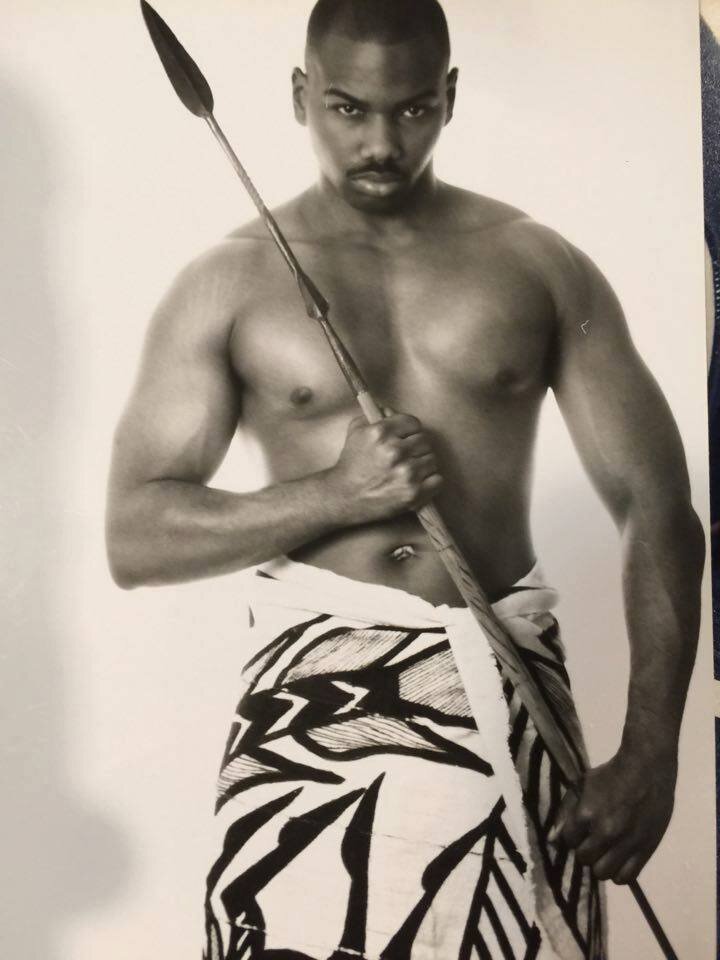

In any case, having lived the pre-teen life of a chubster, I’d already had the experience of a body outsider early on. But, the later teen life of a 29-inch waist twink throughout high school and living as a 32 to 34-inch waisted muscled, club kid throughout my 20s, the weight gain that hit me in my 30s was unexpected, though it shouldn’t have been. Childhood obesity is a predictor for later obesity and the average American man gains 10 - 13 lbs. per year somewhere after age 35. Thanks to a combo of arriving firmly into middle age, living a considerably more sedentary lifestyle than my youth, choosing to abandon the gym hours for the education hours it took to complete both BFA and MS in my 30s, and the hereditary condition of an underactive thyroid that was diagnosed several years after it began doing its damage, here I am, Black Bear: Man of Size. But, the journey to not just say “my body is not an apology” that needs an explanation, but to actually live that mantra’s meaning has been a challenge I’m happy to say is now one that has more positive than negative days. But, even as the founder of an affirming Black Bear social group (Hey, Black Bear Brotherhood of Detroit!), the negative days do indeed somehow persist.

Of course, those days are greatly assisted by the world we live in and the traumatic lives our bodies live through and manifest in various ways. Part of why Gay’s Hunger resonated so much with me is because it nakedly spoke of the sting I experienced when people who knew me dared to ask “what did you do to yourself?” or “what happened to you?” Questions I’ve actually been peppered with more than once by those who’d known me before the expansion of what Gay calls my “unruly body.” These are usually people who had either slept with me, wanted to, or had admired me from afar during my muscular, too tight clothing days. These outraged patrons appeared to feel robbed of their ownership of our connectedness to me as an object of associative value by what appeared to them to be a brazen butchering of a work of “art,” their work of art, temporarily possessed, if only through experience. Instead of someone to boast that they’d once “had” or “hung out” with, I had made myself a disposable, ruined work to be ridiculed and scorned, not someone whose proximity to me lent them cool points of specialness or value.

This value wasn’t all in their heads. Achieving an idealized, muscular body is also a power, one of currency, privilege, and social status, that once achieved many are loathed to give up without a fight or a bout of bulimia mixed with a twist of muscle dysmorphia. This power gets exercised in multiple realms from successful job interviews to coveted party invitations. It also gets exercised in the bedroom, where body worship and power dynamics based on adoration of me and my partners’ bodies was intrinsic to much of the twentysomething sex I had with both muscular and non-muscular bodies when I lived within the skin of the socially desirable and powerful. It took several years to learn how to have sex rooted in domains other than body worship, adoration, and this mutually narcissistic kind of power, even as these dynamics can exist in aspects of every kind of sex, including sex with men of size (they too, shockingly, can be sexually adored and worshipped). But, my mind had to first learn how to appreciate my body in sex before I could let it be comfortably appreciated by others’ intrusive hands and locate their appreciation of my form outside of the undesired realm of fetish and, ironically, objectification. This process too was years long and difficult, for me at least. That I had needlessly put myself through such a process by getting fat in the first place and seemingly thrown away this much-coveted power for a body many envisioned as having not only less power but as socially and culturally weak and powerless, was an astonishment for both the muscle boy community I left behind and those who’d craved admittance to its “VIP” club and its bedrooms. For me, the truth behind my willful disempowerment was more complicated than their reductions.

In Hunger, Gay explains what it meant to have weight serve as a buffer for someone who’d experienced the possessive and violent act of rape. I had been raped at age 14 by a stranger and had come close to having date rapes occur at least two other times in my “more desirable” 20s, but for my then musculature and rage. While I’d later come to learn that there were some medical reasons for my weight gain, to blame it all on my underactive thyroid would be a bit of fake news. As much as weight was physical, it also was psychological, keeping the numbers of sexual partners I had to a figure I could actually count, an impossible feat before age 30, and reducing the likelihood of acquiring one of the STIs that were claiming and sometimes falling the lives of those around me. Not living in “that” body was a way to focus my time and attention on something other than men, their gaze, and centering my life around both, to something more meaningful, nurturing, and sustainable than transitory and unreliable beauty.

Weight was a power too, a choice too, a way of creating a self-protective distance between me and the world. And, here were all these plump and cheerful presences at a Floridian body positive event ripping through all of my self-protective defenses and saying there’s nothing separating us from everything in life: sex, love, lust, risk, desire, disease, affirmation, except what we think of ourselves and how much we allow the world’s attitude about us to define us. And, if my life could be—and actually is—not as different from my thin or muscular counterparts as I’d like to believe it to be (and experiencing just as much jeopardy in the long run), then what protections did I have from the world really? What power did weight afford me now? These are not the ideas one is supposed to harbor at a spring social identity celebration, high on the positive and silent on the haunting specters waiting around the corners of April 21st, after the BBP annual parade passes by.

Which is not to say that BBP and its like should not exist. They absolutely should, despite whatever triggers, processes, and existential questions they may conjure aside. Part of why there are more positive days about this shape of mine has been greatly aided by the emergence of a Black bear culture that has taken it upon itself to radically redefine what it means to be sexy, desirable, and even popular, elevating its own legends, statements, and stars through branding, social media groups, Tumblr pages, and the like. Men whose bodies and appeal exist far outside the acceptable boundaries of not just Black culture or gay culture or even Black gay culture, but American white supremacist culture and its obsession with thin whiteness. From the major events of Heetizm and Tha Big Dogs to Heavy Hitters and Big Boy Pride and all the quieter subsets in between, like my Black Bear Brotherhood potluck in Detroit to the size affirming, kinky brothers of Onyx to the Meet & Greet Big Boy mixers sprouting up all over the land, celebrating Black men of size with an unapologetic Blackness in ways neither their Black gay community nor the white gay bear community counterparts can ever seem to fully bring themselves to embrace. In response to that neglect, a movement has risen and is hitting its stride in arenas beyond just the parties, events, and gatherings, but in the emergence of businesses catering to Black bears and their very discriminating taste and often full wallets and nerd informed pedigrees. There’s a market here, if niche, and it’s starting to recognize not just its own physical beauty, but its power too, as seen by the BBP fashion show spotlight of designers for us by us, the tabling of Black bear businesses selling their wares, and the networking and business card exchanges I witnessed between people looking to do business with one another, extending their pride in other ways.

The advocate in me loved it all, but the more cynical interrogator in me wondered how it could be more…honest. What would it mean in such a body positivity utopian space to have people discuss their ambivalence with their bodies? The fact that after leaving this space of affirmation and acceptance, the afterglow would eventually fade, and a return to big boy social media groups that posted more muscle worship images than that of the girthy men of the body baptismal pool. What would it mean to discuss out loud the ways the encroaching pale, thin, aged and muscular bodies of the Parliament House’s regular weekend patronage, one merely roped off, but ever present every evening, surrounded the BBP festivities like unwelcome, fishbowl spectators on our Black bear fantasy cocoon wrapped in protective blue and gold BBP police tape. What would it mean to say out loud that some of us here were not in love with every roll we see or have and that some were merely faking it out of a desperate need to not experience being the body outsider yet again to one more space that was supposed to love and embrace us just as we are?

I suspect that’s not the role of BBP, a therapist couch perhaps, but there seems to be an effort to provide a kind of Westworld where the big boys have all of the power and none of the pain that awaits them on the other side of that shielding rope.

And, what of me, the one who found more solace in the brazen, if sometimes painful honesty of Roxane Gay’s Hunger than I found in the tireless cheerleading of Taylor’s My Body Is Not An Apology, someone whose natural inclination leans a little more dark and complicated than light and nuance-free. Where do we whose process has not yet led to pumping BBP pom-poms fit?

No event can be the end all and be all for every patron. This should not need to be said, but perhaps must be given the fragility of movements still in their toddler years. Despite my interrogations and critiques, as a BBP first-timer, there was still something incredibly beautiful about the idea of hundreds of Black gay and bisexual men of all shapes and sizes, most on the larger side of the spectrum, affirming one another with their lust, silver-tongued words, and appreciative eyes. There is perhaps nothing more unapologetically Black and subversively queer than watching near naked Black gay men with “unruly” bodies saunter up and down the pool sides casting delicious glances of desire at one another against a backdrop of hip-hop and soulful house. Watching them vibrate in vibrant yellow, a color often seen as too bold and Negroid to be respectable on Black flesh, on the evening that celebrated the brassy “Deeper Love” color scheme of blue and gold. Seeing these powerfully present brothers observe their own Black Panther on “Wakanda Night” by adorning their ample bodies in the flowing cloth, designs, and aesthetics of both the real and mystical Motherland, claiming their part of their rich heritage as kings too, gay and/or femme be damned. To observe them give themselves over to the abandon of the drum in joyous dance to the DJ’s blood beats and sweat as they moved, grinded, and twerked without fear of knowing smiles, quiet condemnation, or the intrusive camera phone filming for later use of social media jokes and ridicule. To have something as simple as another beautiful man step to them in public, in the sunshine, and tell them how beautiful they are. To get to take for granted all that the culture would deny them. And, that nearly 1000 reclaimed their right to these experiences, under streaming banners that demanded a deeper love of themselves and one another was moving.

Others may talk about the less than legendary performance by the iconic Martha Wash, the deadpan jokes of hostess Harmonica Sunbeam, the stimulating wellness workshops, the rafter-shaking big boy church service choir bringing the sacred to the secular, the daily morning workouts belying the idea that size cannot also mean health, the slaying trophy winners of the ball, the athletic earnestness of the sporting event superstars, the sometimes corny competitions celebrating each class of Big Boy Pride attendees so that all newcomers and vets could be reconnected or introduced to the family, and the sizeable number of ever-present slim to muscular chasers serving as allies, admirers, and lovers of these epic men, but what I’ll remember is the pool and the sun. What I’ll remember is the confidence and swagger as the men frolicked and splashed. And, what I’ll hope is that I’ll be among those who’ll take off their shirt next year in the water, under the sun. And, I’ll hope the others who watched alongside me in silence, in fear, in conservatism, or shame joins me in the unmasking of all, all that we are.

L. Michael Gipson is a writer, educator, and 24-year advocate for a host of social justice causes, L. Michael Gipson, MS is the co-founder of the Beyond Identities Community Center for LGBTQ youth in Cleveland, the Black Alphabet Film Festival in Chicago, and the Black Bear Brotherhood in Detroit. Currently, Gipson is the Founder and Principal of Faithwalk, LLC and the Urban [W]rites project. A Red Dirt Press author, Gipson serves as Editor-at-Large at SoulTracks.com and Lead Writer and Co-Producer of the PBS docuseries Indie Soul Journeys.