Gains & Pains: Black Gay Bodybuilders & the Complex Dynamic Between Muscles & Queer Desire

Despite an active childhood that included playing football and running track since fifth grade, Gerald Thomas was a bit spooked when he read his class schedule at the start of his freshman year at Elbert County Comprehensive High School in northeast Georgia.

“When I saw it said ‘weightlifting’ I went to my school counselor and asked her to change it because for some reason I was intimidated,” Thomas recalls. “She told me that for all athletes, weightlifting was our P.E.”

Thomas’s aversion to bench presses and squats soon dissipated as he became a stronger defensive end, a faster 400-meter runner, and experienced other benefits of regularly being in the gym.

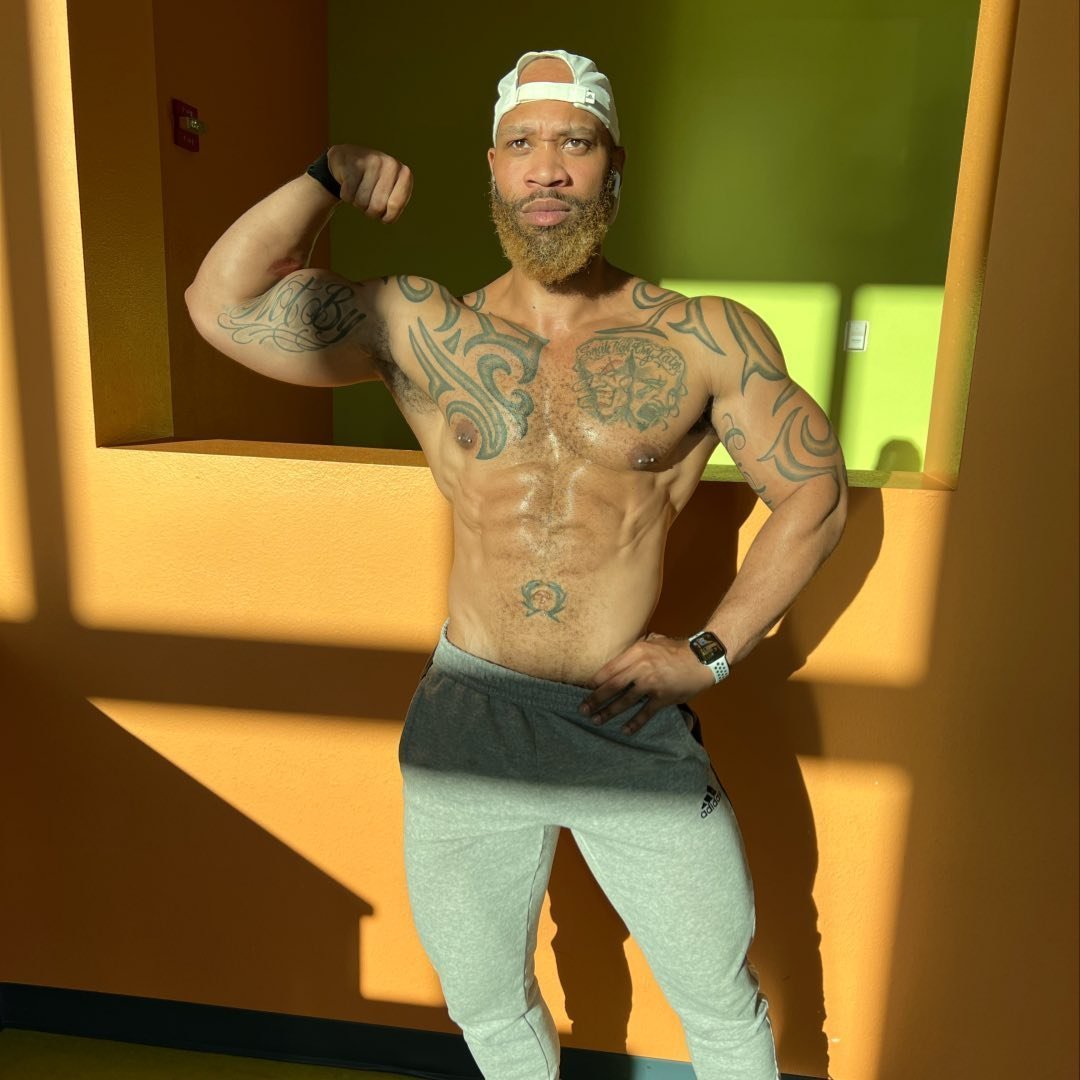

“It helped me improve my performance, and it also made me look better,” says Thomas, who more than 30 years later remains an avid weightlifter, and whose 50-year-old physique resembles that of a college athlete. He briefly stopped working out after ending his collegiate track career, but within a month, Thomas noticed the activity he once dreaded had become an essential part of his being.

“When I stopped working out, I felt some type of gap in my life,” he says. “I realized that was a part of my everyday routine and something I was used to, part of my lifestyle. In the beginning, weight lifting was just a stress reliever—whenever I would go to the gym, I would just feel so much better afterward.”

“When I stopped working out, I felt some type of gap in my life. I realized that was a part of my everyday routine and something I was used to, part of my lifestyle. In the beginning, weight lifting was just a stress reliever—whenever I would go to the gym, I would just feel so much better afterward.”

- Gerald Thomas

That post-workout euphoria is familiar to Marcus Saulsberry, who described himself as a high school and collegiate band geek before he first started going to the gym about a dozen years ago.

“I was very slender and small, and lifting weights was not my forte—push-ups, I hated,” Saulsberry, 36, recalls with a laugh. “We had to stay physically fit [for the band]—we ran, we marched, jumping jacks, that’s about it.”

Calisthenics hadn’t prepared Saulsberry for his first months at the gym, and it took years of starts and stops before he no longer hated lifting weights.

“Because it hurt!” he says in a tone recognizable to anyone who has ever heard their muscles scream. Saulsberry’s motivation also waned in those early years because, like many, he expected to start looking ripped after a few weeks of pumping iron.

Saulsberry didn’t begin seeing changes in his physique until about three or four years into his fitness journey, and by then going to the gym had evolved into much more than working out.

“I’m a very social person, so meeting people, getting feedback from people who you might aspire to, getting advice or just saying, ‘Hey, how are you doing’ to your regulars, that’s really where the love grew,” he says. “I’ve met great people in the gym, some great friends. I’m talking about extra-straight people and friendships that I never knew would come about from the gym. They respect me and my lifestyle and my quirks, my gayness, my femininity, everything in the gym. We’re boys, and they respect me and I respect them. The vibe, the people that I came across, that’s really what made it change for me.”

Gay Muscularity Desired & Vilified

Throughout modern queer history—from the Castro Clones of the 1970s, the porn and cover model aesthetics of the last four decades, to the preferences listed in many online dating profiles—gay men have had an ambivalent relationship with muscularity. Men with chiseled chests and eight-pack abs have long been considered the default standard of homosexual desire, and as a result, the embodiment of a fantasy that is partly blamed for higher rates of body image anxiety among gay men.

“A greater percentage of gay men than heterosexual men reported that they were unattractive, uncomfortable in a swimsuit, dissatisfied with their physical appearance, and dissatisfied with their muscle size and tone,” says Dr. Jamal Essayli, a psychologist and assistant professor at Penn State College of Medicine who co-authored a study on male body image issues in 2016. “In general, both gay and heterosexual men reported poorer body image as [body mass index] increased.”

“A greater percentage of gay men than heterosexual men reported that they were unattractive, uncomfortable in a swimsuit, dissatisfied with their physical appearance, and dissatisfied with their muscle size and tone.”

While gay men are not alone in feeling like they do not measure up to standards of beauty, feeling sexually undesirable can be uniquely alienating when one’s connection to a community is somewhat predicated on sex, says Dr. Carl Hovey, a psychologist, and researcher at the Gay Therapy Center in New York.

“Inclusion in the community depends on one's ability to ‘live out’ one's sexuality through certain relational encounters; and if one is not experienced as desirable, the feeling of being cut-off from the community, and even from one's identity, can be profound,” says Hovey, who believes the beauty standards of the larger society, and among gay men, also exert pressure on those who fit the standard.

For Saulsberry, going from lanky to swole felt comparable to someone joining a Black Greek-letter organization in college. Some men start acting like a big man on campus the moment they cross the burning sands, and Saulsberry noticed how some people began expecting his ego to grow as big as his muscles.

“I pride myself on being one of those people that didn’t change just because you look a certain way,” says Saulsberry, who has nonetheless been treated differently by people as he has bulked up.

“I’ve been called a muscle head, I’ve been called a jock,” says Saulsberry, a former drum major and J-setter whose flamboyant behavior can draw confused side-eyes. “People perceive you just because you have muscles, you’re masculine, or you’re a top, or you’re not supposed to dance a certain way.”

“I’ve been called a muscle head, I’ve been called a jock. People perceive you just because you have muscles, you’re masculine, or you’re a top, or you’re not supposed to dance a certain way.”

- Marcus Saulsberry

Friends have told Thomas his desirability makes him undateable, that a swimsuit model could not withstand the waves of sexual opportunity that must wash over him every day.

“A lot of time I think people don’t trust me because of my looks, or they don’t take me seriously,” Thomas says. “They see me as a sexual being, not so much as boyfriend material, just based on how you look.”

However, Thomas recognizes that being objectified for his physique has also provided unfair advantages in other parts of his life.

“It’s sad to say it, but I have been event planning and catering for stores mostly in Lenox and Phipps [malls in Atlanta], and basically they don’t really hire you on your talent. They hire you based on how you look and the talent comes next.”

And this may be why there are countless think-pieces and empowerment campaigns that condemn the effects of gay beauty standards on those who feel they fall short of them, but little empathy when those who seem to meet those standards are degraded as being dumb, shallow, or sexually promiscuous.

“All individuals are nuanced, multi-faceted and complex, and it’s inaccurate and unhelpful to perceive anyone as a stereotype, such as assuming someone’s life is fantastic because they look a certain way.”

“Overall, the privileges and positive attention [muscular gay] men receive for their figure outweighs any negative judgment they might receive,” says Essayli, who elaborates to note that being considered hyper-desired does not mean someone’s life is easier or better.

“All individuals are nuanced, multi-faceted and complex, and it’s inaccurate and unhelpful to perceive anyone as a stereotype, such as assuming someone’s life is fantastic because they look a certain way,” Essayli says. “Feeling boxed-in or stereotyped in any way is potentially harmful [and] individuals who look more ‘physically ideal’ can experience the same, or greater, mental health struggles than others do.”

‘The Best Me That I Can Be’

One of the more unjust prejudices against muscularity is how well-sculpted individuals are reduced to one dimension, as if the discipline, commitment, and sacrifice required to attain such a physique does not translate to other parts of their lives.

“It takes a lot of dedication and a lot of time,” says Thomas, who notes that diet is just as important as the gym, which adds hours of meal prep to the overall fitness schedule. Having recently marked his first year of competitive bodybuilding, Thomas’s routine can now reach three workout sessions per day, including training with a weightlifting coach and another coach for competitive posing.

“Before, I was just [lifting weights] for fun or for my own benefit and as a stress reliever, but now it’s more of a job because I’m on a team now,” says Thomas, who won both his category and the overall competition at his debut bodybuilding contest in June 2021.

“It’s something I enjoy. I feel good about myself for being the age I am and being able to look the way I look.”

“I’m not looking to be perfect for someone else. I’m looking to be the best me that I can be. If anybody is looking for the accolades or affirmations of others, then that’s already the wrong start, I feel.”

- Marcus Saulsberry

Saulsberry, who considers working out as routine as taking a shower and brushing his teeth, has set a goal of competing in two bodybuilding contests in 2022—where the standards for the perfect body are exponentially harsher than on any gay dating app. Saulsberry plans to protect himself from unrealistic expectations with the same philosophy that has guided his fitness thus far.

“If you feel like you’re bringing your best package, or you’re bringing your best body to the stage, then I assume that you’ve accomplished what you wanted to do,” he says. “I’m not looking to be perfect for someone else. I’m looking to be the best me that I can be. If anybody is looking for the accolades or affirmations of others, then that’s already the wrong start, I feel.”

Ryan Lee is a freelance writer in Atlanta and a columnist for The Georgia Voice, which focuses on LGBTQ issues in the south.