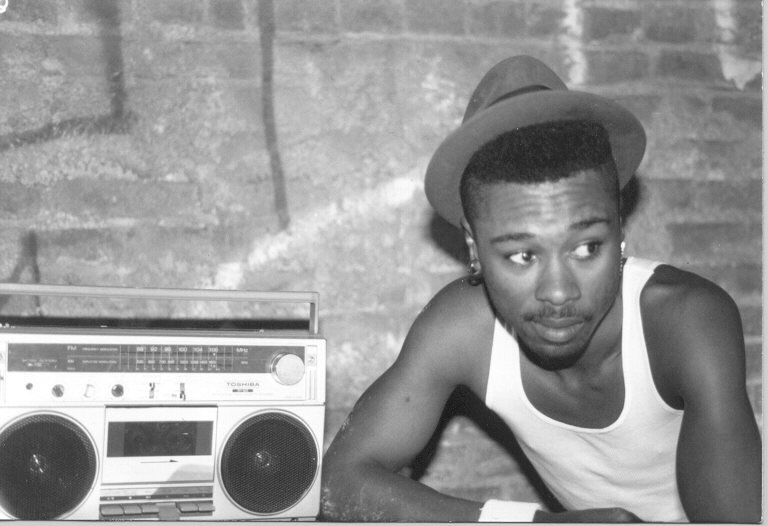

Songwriter Kipper Jones On Penning Hits For Brandy, Vanessa Williams, and His Journey to Liberation

If Kipper Jones, 59, could go back in time to give himself advice, the celebrated songwriter and vocalist says he would simply say, “don’t be afraid.” For the man who famously penned hits for Vanessa Williams (“The Right Stuff,” “Comfort Zone'') and Brandy (“I Wanna Be Down,” “Brokenhearted”) that catapulted their careers and made them superstars, Jones has spent most his life running towards success and running away from himself. As a self-identified same-gender-loving man, Jones often wrote about love in songs that shot up the Billboard Hot 100 chart, while denying himself the experiences in his lyrics.

“I’ve kind of had arrested development in some areas of my life in terms of relationships. I didn't even delve into that until way later in my life,” says Jones, who adds that he didn’t pursue relationships in his early 30s because he felt like he couldn’t.

Before Los Angeles became his second home and recording studios across the city his haven, Jones found inspiration, honed his musical chops, and received societal cues about people who were different inside the sanctuary of New Jerusalem Baptist Church under the leadership of Rev. Otis Floyd in his hometown of Flint, Michigan.

“They say he was a blues singer in his previous incarnation, but man, he just had all this soul when he sang,” says Jones of Rev. Floyd. “My mother says I would just sit there and just marvel at him. I remember that,” he says.

But for Jones, it was Jeffrey LaValley, a then “17-year-old kid from Milwaukee who just came to town and blew everybody away,” that he credits as his first real musical influence.

“Jeffrey was writing songs for the choir and he was 17. I'm like, he's so talented. How do you do that? Where does that come from? I saw him do it and I think that was my first visual of it,” says Jones. “Just how to take an idea and make it a song and give it to people and teach them how to do it. It was just incredible to me.”

Jones would be given many opportunities to display lessons learned and to build upon LaValley’s musical influence after relocating west to Los Angeles with his family, which put him in the right place at the right time, in the studio with a former Miss America who would use success as the best revenge after being forced to relinquish her crown, and alongside an untested young singer with only a failed sitcom that ran for one season as her biggest credit. Jones had the right stuff and soon everyone would know it.

The Hitmaker

In 1994, the year the world was introduced to singer Brandy [Norwood] after the release of her self-titled album, Jones had already achieved double-platinum success with Vanessa Williams, and two of his songs had been placed on the soundtrack for the Robert Townsend film The Five Heartbeats. So Jones says he was naturally “feeling himself” and uninterested in “some little girl that people don’t know” to sing a new song that he and his producing partner Keith Crouch immediately knew would be a hit and one that Jones intended to go to Williams.

“I went to his [Keith Crouch] house one day, and this track was playing, and I'm like, what the hell is that? And he was like, ‘it's just something I'm working on.’ And I was like, have you written it yet? And he said, ‘no, you want to do it?’ And I was like, yeah,” recalls Jones. “So I went to the car, got my notebook, and came in. We are in Keith's apartment in Studio City, and it’s myself, and Keith, his brother, Kenneth Crouch, and Rahsaan Patterson, and a few of our female friends, probably about four or five people in the room. I had a bottle of Hennessy, and I got this hook in my head,” says Jones as he sings.

“I wanna be down with what you’re going through…”

“I said, hey, let me put this verse idea down real quick,” says Jones to Crouch. He said, ‘okay.’ So I did it. And then that chorus played and Keith just stopped the recorder. And we just stood there. We were like, oh, snap! I think we just did something.”

Jones tells The Reckoning that he’d never felt the way he did after finishing “I Wanna Be Down,” but he was still unconvinced that an unknown singer that he’d never heard before had the talent to contribute the vocals.

“Keith was like, ‘Kipper, let the girl demo the record. What is it going to hurt?’ And I'm like, oh, okay. You go do it. Take it to her, and just let me know when you're done.”

Jones’s tune quickly changed after hearing Brandy’s vocal on what would become her debut single.

“That baby wore me low,” he says. “I was like, what? She's how old? 14? She can't be 14 singing like that.”

Jones’s reaction was a precursor to how the rest of the world would react to the young singer who would be crowned the vocal bible by fans. “I Wanna Be Down” would also become one of three songs requested from Jones and Crouch by music industry executive Sylvia Rhone for Brandy’s debut. “Best Friend,” originally planned as a duet with brother Ray J, and the hit ballad “Brokenhearted,” also made the album, causing upset from other songwriters whose songs were removed to make room for Jones and Crouch’s work and the biggest writing challenge of Jones’ career.

“I was just drawing blanks. That's one of my biggest writer's block moments,” recalls Jones of writing “Brokenhearted.”

“I was so frustrated with this thing. I was crying. Because when you have a deadline, nobody cares about how you feel. We have a deadline, which means you have to make it or move, let somebody else do it. I went out in my car and drove around—nothing. I got back home, and I was in the driveway and I just broke down, and I'm like, Lord, it's got to come. And I had to go back through my process again.

Jones says his process of writing for singers begins with finding answers to key questions.

“Who is she? Okay. She is a 14-year-old female R&B artist. So who is her audience? Other 14-year-old females, right? Kids sing to kids. What do they talk about? 14-year-old girls talk about boys. That's it. They don't talk about anything else, they talk about boys,” he says as he scribbles on an imaginary pad and pen to illustrate the notation of his answers.

“They're not talking about sex, she's 14. But they have crushes and they get their heartbroken,” he says. “So what do you tell other 14-year-old girls? Well you get your heartbroken and you get over it,” he says.

And then a lightbulb goes off and Jones continues to write on his pad while verbalizing— “But I guess I'm only brokenhearted, life’s not over. I can start again.”

“And it just started coming out like a stream of consciousness, I swear to you,” he says as he sings.

“I’m young, but I'm wise enough to know... that you don't fall in love overnight. But as soon as I closed my eyes, I was saying to love goodbye.”

“Brokenhearted” was a top 10 hit that increased in popularity with the addition of Wanyá Morris (Boyz II Men) on the remix, and was recorded by an eager 14-year-old Brandy in one take, according to Jones.

“She wanted to go to Magic Mountain with her friends. All her friends were going, and she was supposed to be coming to the studio, and she was hot about it,” he says. "That baby did that song in one take. I mean, we did some little fixes cause that's the one I produced the vocal on. But basically, that's a one-take vocal,” says Jones.

“I subscribe to the African proverb that says, no one ever dies as long as someone living says their name.”

The Path To Liberation

Having achieved major songwriting success in Los Angeles starting in the late 80s, Jones left the west coast in 2000 and landed in Dallas for six years before ultimately moving to Atlanta. It was in Dallas at Friendship-West Baptist Church under Rev. Dr. Frederick Haynes, III that Jones reconnected with his spirituality and began to define himself in the absence of fear.

“I had a chance to investigate and delve into who I am. The things that I was afraid of, the things that I was running from,” he says.

Jones says he was now surrounded by other gay Christians at Friendship-West and approached Haynes to gain clarity regarding his apparent acceptance of LGBTQ+ people.

“He said, ‘Kipper, it's really simple—there is a passage in the Bible that says, whosoever will let him come and drink of this cup, whosoever will.' And he looked at me and he said, ‘I'm gonna go with that.’ He kept it real with me,” says Jones. “He said ‘Kipper, these folks ain't got a heaven or hell to put you in. Don't let them do that to you. Take your power. Do not let them do that to you.’”

“I had a chance to investigate and delve into who I am. The things that I was afraid of, the things that I was running from.”

Besides embracing Black liberation theology as it applies to his experience as a Black man in America, Jones also applied the same principles to free himself from the internal and external chains of being a Black same gender loving man, which he says Haynes played an instrumental role.

“Hey, you're going to be okay as soon as you realize that what you do is not who you are,” Jones recalls Haynes saying.

“That thing set me on a path,” he says.

Now, Jones says he is living in possibility and reveling in the past and present of his journey while acknowledging that he has created art that will live beyond his existence in the physical realm.

“I subscribe to the African proverb that says, no one ever dies as long as someone living says their name.”